SEATTLE — New research from the University of Washington dives into the minds of mosquitoes to understand how they find their targets.

To see what happens inside a mosquito’s brain when it’s looking for blood, scientists at UW placed leashes on mosquitoes and put them inside a miniature stadium where they could manipulate the sights and smells.

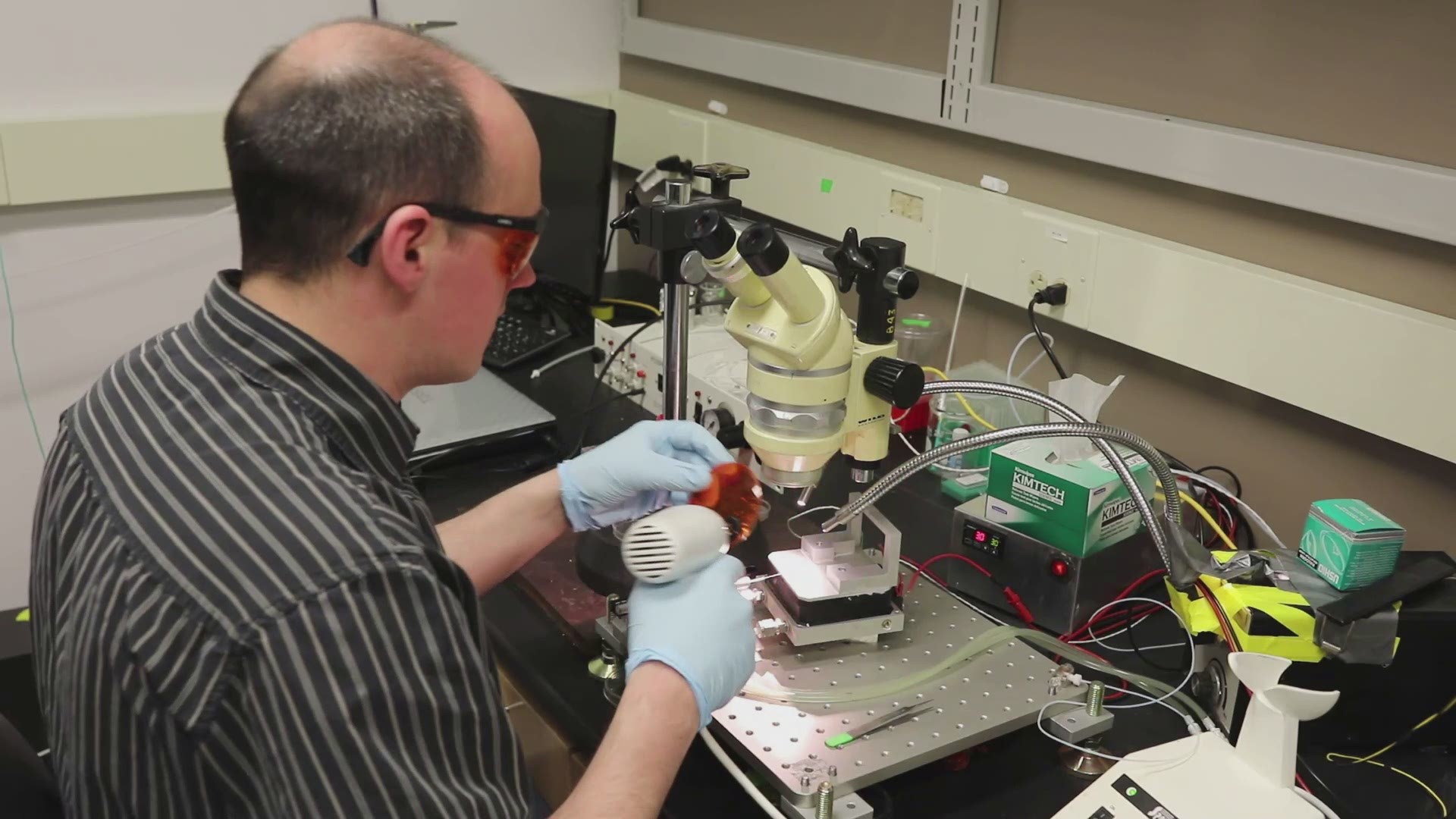

“We put mosquitoes in this virtual reality environment -- we call it a flight simulator -- to look at the behavior of the mosquito when it’s tethered and flying in place,” explained Dr. Jeff Riffell, a professor of biology at UW, who conducted the experiments.

The mosquitoes in question were genetically engineered so different parts of their brain would light up green when active. The scientists also removed a portion of the mosquitoes' skulls and used a special microscope to watch as the mosquitoes responded to different stimuli.

“Mosquitoes impact more than a billion people a year and cause mortality of more than 500,000 people per year,” said Dr. Riffell when asked about why the research is important. “There’s increasing insecticide resistance, and due in part to climate change, there’s changes to where these diseases spread and there are new diseases arising.”

What they found

When a female mosquito gets a whiff of carbon dioxide, its brain switches into hunting mode. Its vision and smell centers kick into high gear, and its wings start flapping faster as it tries to fly upwind to the source of the carbon dioxide.

Mosquitoes are also drawn to dark colors and high contrast, and they became more sensitive to these visual cues after smelling carbon dioxide. But exposure to visual cues alone, like seeing dark colors, did not trigger the same type of heightened senses that resulted from smelling carbon dioxide.

Mosquitoes mostly feed on nectar from flowers, but the females need blood to produce their eggs. A mosquito’s sense of smell is very different from a human’s—they can detect carbon dioxide from up to 100 feet away. Humans are constantly breathing out carbon dioxide, so we can’t smell it, but that is exactly why mosquitoes are sensitive to it: it helps them find us.

“They can also sense heat and humidity from our sweat, so it’s like a guided missile triggered by that initial whiff of carbon dioxide,” said Dr. Anandasankar Ray, an associate professor at University of California Riverside, who was not involved with the research.

The researchers used the Aedes aegypti mosquito, commonly known as the yellow fever mosquito, it’s also responsible for the transmission of dengue and the zika virus.

The research on mosquitoes' attraction to carbon dioxide means obscuring the smell of carbon dioxide could help develop new ways to repel the pests.

“I’m excited because there’s a host of odors that interfere with carbon dioxide reception, so this research shows that they could be very effective,” said Dr. Ray.

Why do some people get bit more than others?

There are a few factors at play, including some you can control and some you can’t.

Researchers said wearing light-colored clothing will help reduce your appeal since mosquitoes are more attracted to dark colors and high contrast.

Carbon dioxide aside, mosquitoes are also drawn to the scent of humans. This isn’t just your sweat, it’s also the bacteria living on your skin – called “skin microbiome” – that produces your body’s smells. Skin microbiome is largely controlled by your genes. Why some people’s odors are more enticing remains a mystery, but if you’re one of those unlucky people, showering can help cut back on your mosquito-alluring scent.

The fact some people get more attention from mosquitoes than others isn’t just bad for them, it also contributes to the spread of disease. If one of those popular people is infected with a disease, they are also more likely to spread the disease to more mosquitoes -- compounding the disease-spreading effects.

For the time being, DEET remains a popular and effective mosquito repellent. While there have been some concerns about the health effects of DEET, Dr. Ray says there haven’t been conclusive studies showing negative health effects and it’s generally considered safe. However, there are still a few drawbacks.

Getting full coverage on exposed skin is important. DEET does repel mosquitoes, but they only start to smell it from about half an inch away, so if you miss a few inches of skin, the DEET on the rest of your body won’t protect you. Alternatives that could obscure the smell of carbon dioxide could have the potential to be more effective over greater ranges.

DEET is also a power solvent, meaning it can stain and damage leather or synthetic fabric, melt your plastic watch, or strip the paint from your car. When applied to your skin, DEET will make its way into your bloodstream.

Dr. Ray said he’s personally made the switch to effective natural alternatives, like lemon-eucalyptus based bug sprays.

As our understanding of mosquito behavior continues to improve, Dr. Ray’s hope is we’ll find better ways to control them.