PORTLAND, Ore. —

The fall of 2020 was a tough time for many on the West Coast. Thousands were displaced by wildfires, and even for those who weren’t, thick blankets of smoke became part of daily reality for thousands more.

“I don't think we saw the sun for several weeks,” said Elizabeth Tomasino, a professor of enology and food science at Oregon State University.

The smoke was dangerous to public health, but it was also catastrophic for the wine industry, which saw an nearly $4 billion in losses from what’s come to be known as “smoke taint.”

“When there is wildfire smoke in the vineyard when there are grapes on the vine, the compounds in the smoke that make it smell like smoke get absorbed into the grape,” Tomasino said before describing some of the resulting flavors. “I perceive it as a mouthful of cigarette smoke or a day-old campfire, which is not something you want in your Oregon pinot noir.”

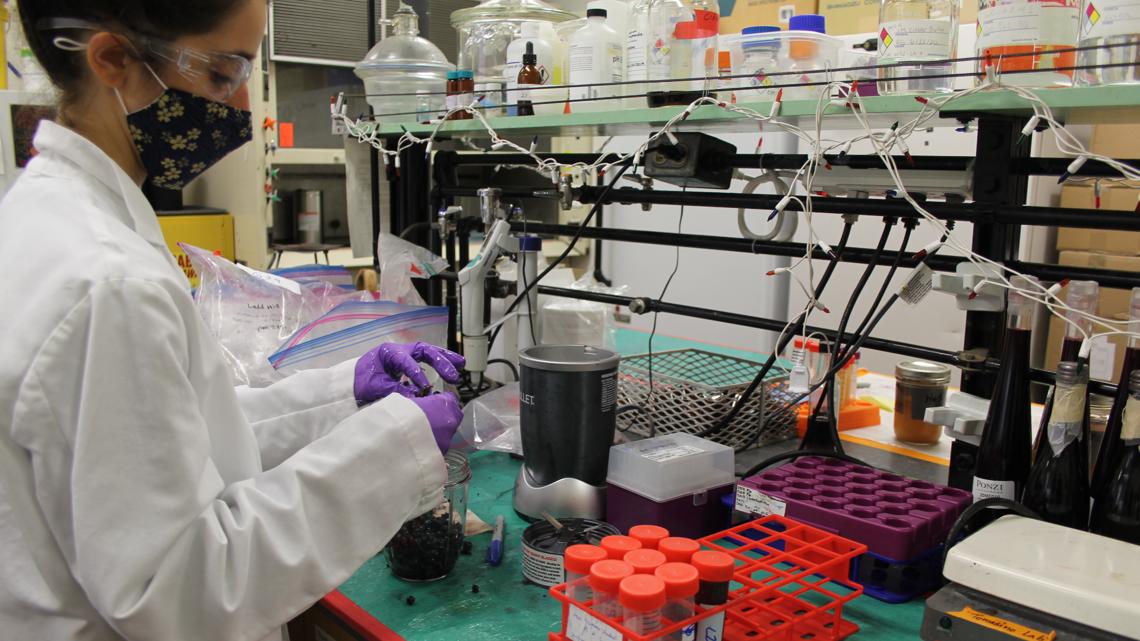

So Tomasino and a team of researchers at Oregon State set out to find a way to protect grapes from absorbing the chemicals in wildfire smoke, called volatile phenols, that impact flavor.

Yanyun Zhao, a professor of food science technology at OSU, has been studying food coatings for more than 20 years, and she saw the potential for a solution.

She noted that edible cellulose food coatings are well established technology, used for elongating shelf life and preserving foods.

“It's really not only developing the technology, but really trying to understand the mechanisms, the principles,” she said. “What's the best strategy for trapping the smoke phenol so it will not get into the wine grapes.”

Working together, Tomasino and Zhao developed several formulas of cellulose coating — made of wood plant and fruit fibers — that had the potential to either block or absorb the phenols.

“When you block it, it's like a sunscreen,” Zhao said. “You block the smoke so it’s not even getting into your fruits at all.”

With their formulas in hand, Tomasino and Zhao turned to Alec Levin, a viticulturist who also serves as the director of OSU’s Southern Oregon Research Center, where the school runs an experimental vineyard.

The first step for Levin was to make sure the coating, which can be sprayed onto grapevines, wouldn’t impede growth or otherwise interfere with the growing process.

“The first thing we want to make sure, the baseline, is do these formulations, for lack of a better word, ruin the fruit in any way,” he said, adding that early experiments showed no detrimental effects on the grapes.

Then it came time to test how the coatings held up to actual smoke.

“Whenever there's a problem, the first step is to try and recreate the problem and control the problem so that then you can figure out how to solve the problem,” Levin said, “but I'm not going to go around starting wildfires.”

To simulate a wildfire, Levin and his team constructed rudimentary smoke chambers over the grapes using PVC pipe, greenhouse siding and the kind of small barbeque grill you might have in your backyard.

With the grapes thoroughly smoked, the fruit was sent back up to OSU for Tomasino and Zhao to analyze.

The results were promising, though not quite up to blocking all the phenols the researchers had hoped.

Levin said there are still some questions remaining about practical application given how viscous the coatings are.

“How do they behave out of a sprayer?” he said. “How do you direct them properly onto the fruit and at what time?”

Still, Tomasino was confident that with some tweaks to the formula, the coatings would provide the protection wine growers have been searching for.

It’s no longer a question of whether the coatings will work, just how soon.

“Despite how long it might take and everything we've done with the foundation, with the new discoveries, it is going to be successful eventually,” Tomasino said.