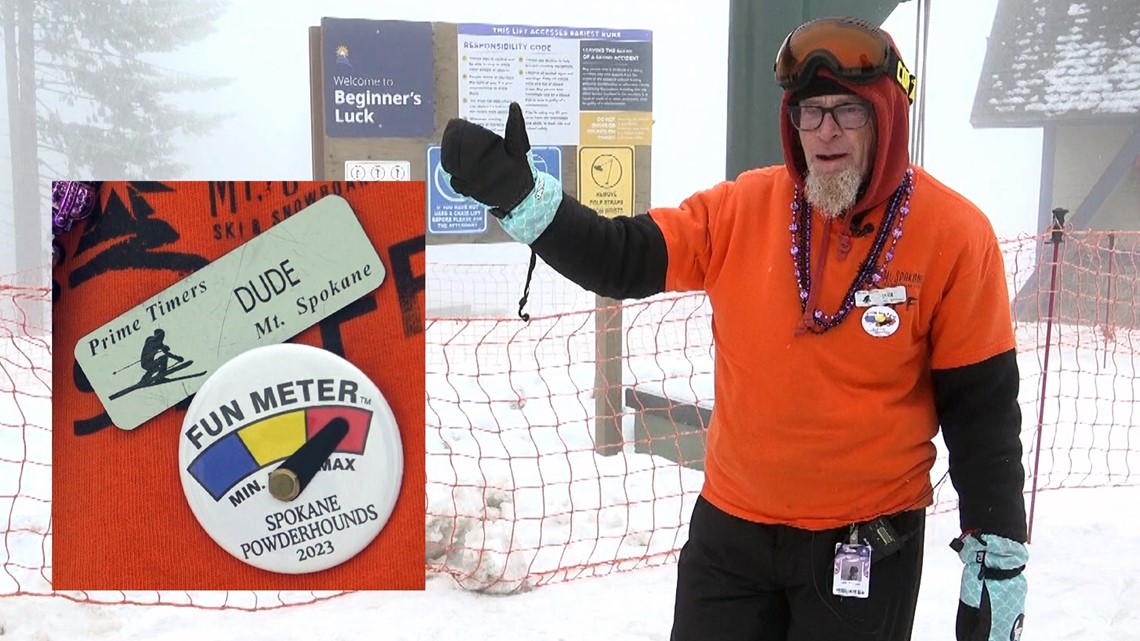

SPOKANE, Wash — There are a lot of places to ski in the Northwest, but there is only one 'Dude.'

For decades, Dude has been operating the lifts at Mount Spokane Ski & Snowboard Park in eastern Washington.

"You learn to deal with the elements," he says.

And this year, the elements have not been the best; ask Dude and he'll tell you.

"Slushy and wet... And then we have snirt. Which is snow-dirt mix."

Dude has a lot of ways to describe the snow, but there is one word he won't use.

"Previously frozen, liquified precipitation days," he calls them. "Because we don’t use the 'R-word' up here."

On this particular February day, snow is falling at Mount Spokane, but Dude knows it's not nearly enough.

"We're right now, I think, at about 55% normal snowpack," Dude says. "It's at 46 inches currently, so we're well below."

More than halfway through winter, the mountains of eastern Washington and north Idaho are under moderate and severe drought due to the lack of snow on the ground.

But this lack of snow isn't necessarily a new thing; Dude can recall several years of early closures.

"2003, 2004 season, I believe they closed on Valentine’s Day," Dude remembers. "2013-14 season we suspended mountain operations the Sunday before Presidents' Day."

And USDA data backs Dude up. It shows a decrease over time in the Snow Water Equivalent at SNOTELs around the region.

Between 1955 and 2022, all stations in eastern Washington and north Idaho recorded a reduction in peak snowpack. That number is just over 20% in higher elevations, while one lower elevation station in north Idaho measured a drop of more than 70%.

But it's not just the overall amount of snow; it's also how long that snow sticks around.

Between 1982 and 2022, the Northern Rockies saw an average decrease in about 15 to 20 days per season of snow being on the ground. So, not only are we not getting as much snow, but it's also not sticking around as long, and early spring warmth is melting it much faster.

These changes already impact mountain runoff, increased fire danger, and longer fire seasons.

Or, to put it another way-

"I think the biggest impact is going to be environmental[ly]," Dude says. "It all depends on mountain snowpack. It's so important, especially for this region."

Rain Shadow

While snow is possible in most areas of the Northwest, how much any one spot gets is significantly influenced by our mountains.

The mountains of eastern Washington, eastern Oregon, and north Idaho sit in the rain shadow of the Cascades, while the Pacific Ocean serves as an excellent moisture source for much of the western side of those states.

As that moisture moves from west to east, or zonally, it first hits the mountains, pushing upward. That rising motion in the atmosphere causes the warmer moist air to first cool, then condense, forming clouds, and eventually precipitation. That changes the amount of rain or snow you see in the Cascades, giving you more than you otherwise would and squeezing out more moisture than you otherwise would get squeezed out.

But as you move up and over the mountains, all that air has to come back down. This sinking motion quells cloud cover and precipitation, leaving much of central Washington and Oregon in a rain shadow or a desert.

But as you move east from there, things get interesting once again. As elevation increases in eastern Washington, rain and snow become more prevalent. Once again, an increase in elevation enhances precipitation.