WELLPINIT, Wash. — Decades after the Midnite Mine ceased operations, the environmental and cultural impacts continue to weigh heavily on the Spokane Tribe and the land they call home.

Cleanup efforts are ongoing at the former uranium mine, located along the Spokane River on the Spokane Reservation, as tribal members grapple with the fallout of a mining legacy that began 70 years ago.

The mine, which was operated by Dawn Mining Company, produced 5.3 million pounds of proto-ore between 1954 and 1964. The environmental consequences, however, have outlasted its operation, with contamination from radioactive waste and water runoff still posing significant hazards.

“It’s hard to fathom that a mineral is worth someone’s life,” one tribal member reflected. “But when you’re an industry that destroys our mother nature, that’s the cost.”

The site includes four open pits, which have historically suffered from issues like radioactive water accumulation. Efforts to mitigate these impacts have been extensive, including the installation of containment ponds and a geomembrane in one of the pits. Despite progress, concerns persist.

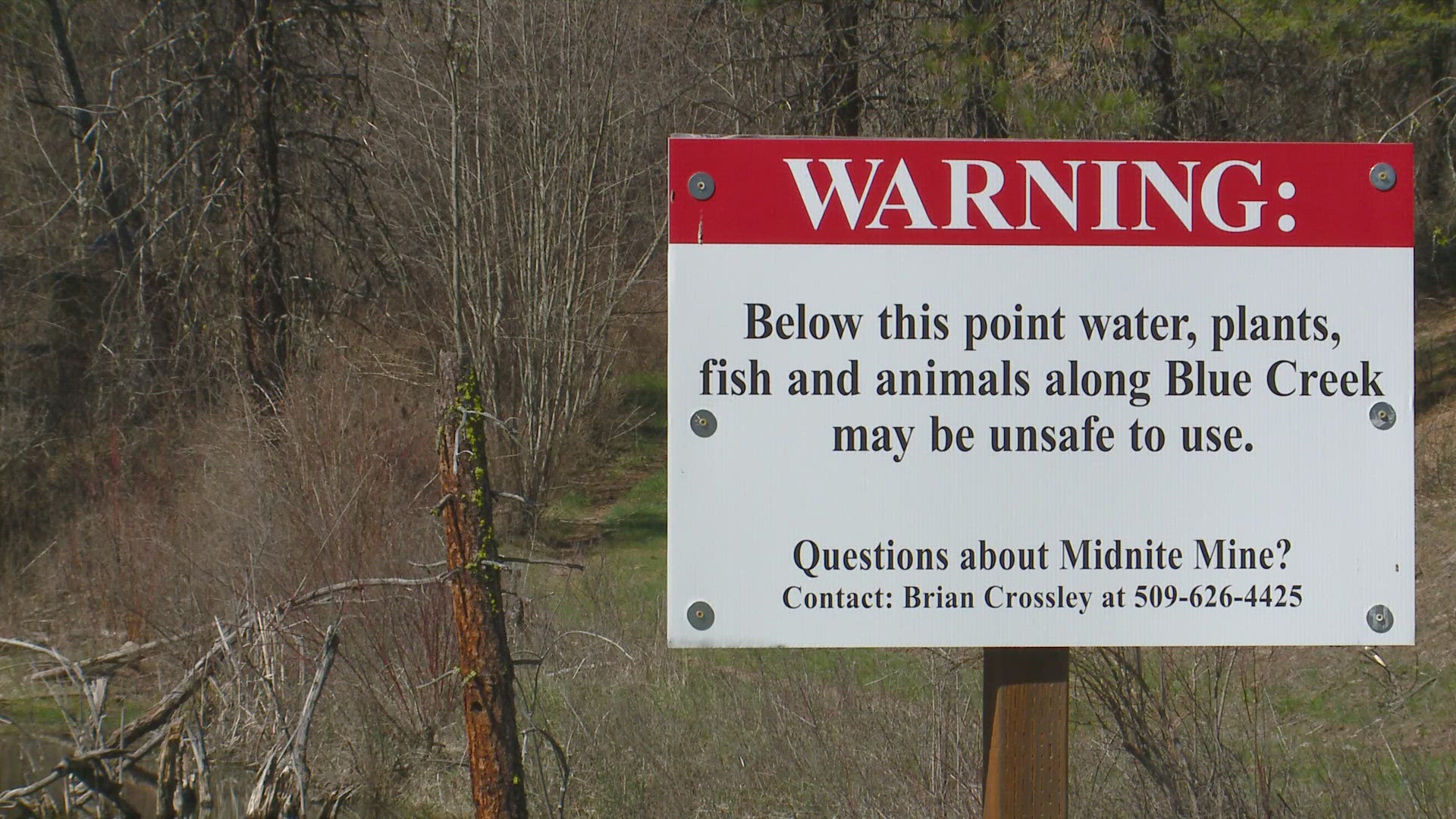

In 2010, the Federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry classified activities using water from the nearby Blue Creek Drainage as public health hazards. Blue Creek, once a beloved recreation spot for tribal members, is now marked by signs warning visitors of contamination.

“We posted the signs to not have access and to not use that water for those purposes,” explained Linda Meyer, the EPA’s remedial project manager for the Midnite Mine Superfund Site.

The Spokane Tribe, deeply connected to the land and its resources, has set the highest water quality standards in the nation. Ricky Sherwood, a tribal member who grew up swimming in Blue Creek, reflected on the area’s transformation. “Every summer, this was where we would go. Now, it’s hard to see those signs.”

Economic necessity drove many tribal members to work at the mine, which offered one of the few employment opportunities in the area. However, this came at a steep cost.

“The thing about the mine people kinda fail to understand when they say, ‘Why would you go there?’ You have to feed your family,” one former miner shared. “It was the only job on the reservation, the only job for miles around.”

While the EPA estimates that major components of the cleanup will be completed by 2026, Meyer emphasized the importance of thoroughness over speed.

“I believe that it’ll be completed within five years, but I’m not in a rush. I want it done right. I don’t care if it takes another eight or 10 years — it has to be done right,” Warren Saylor, a tribal member, said.

For the Spokane Tribe, the hope remains that the land will one day return to its former state, free of contamination and safe for future generations.

“We can always learn from the past to make a better future,” Saylor said.