TACOMA, Wash. — Buried in a Tacoma man's basement are baseball memories he sometimes wants to bury completely.

On one hand, they are historic. On another, catastrophic.

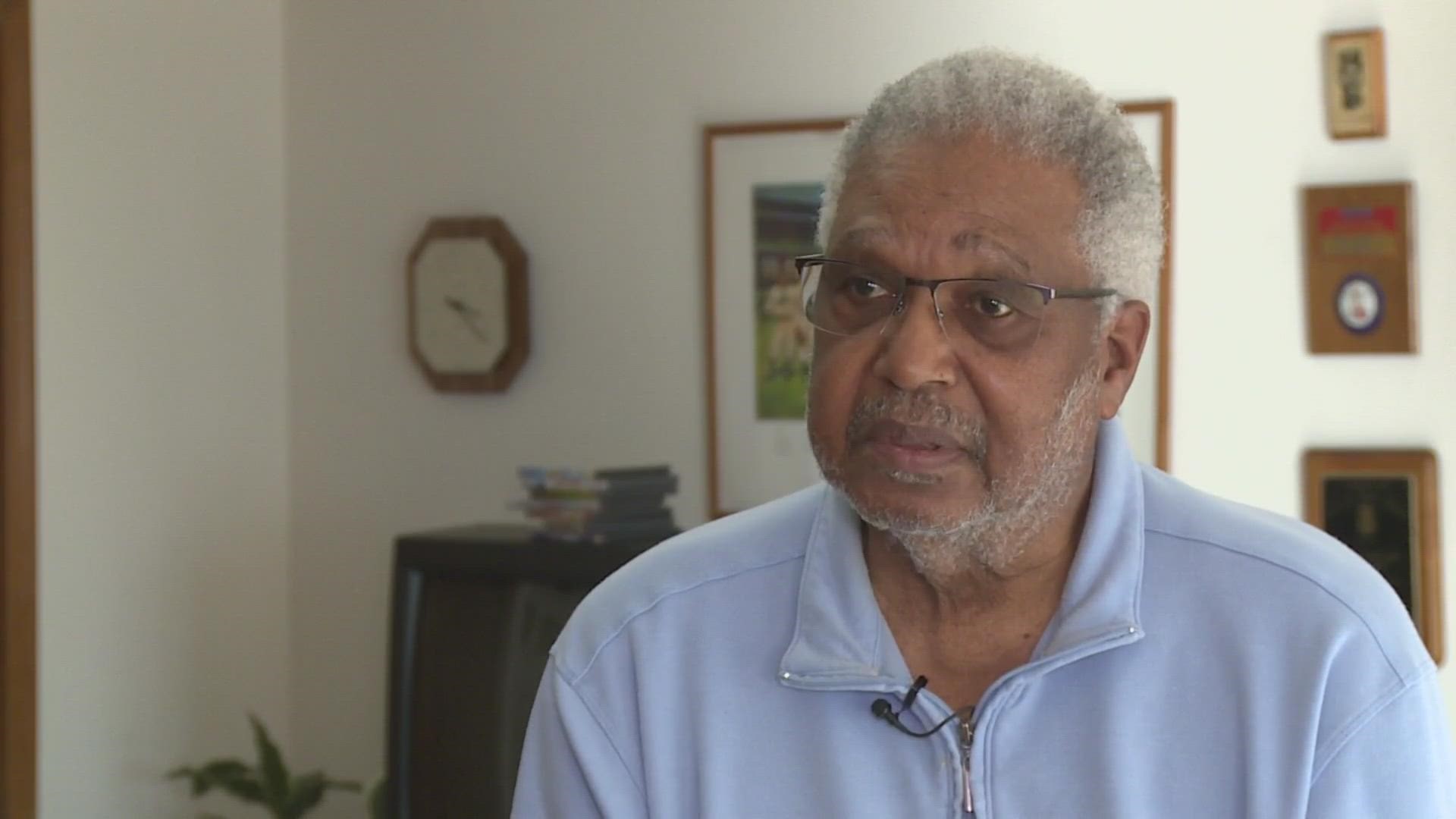

"Those are some things you don't forget," Aaron Pointer said.

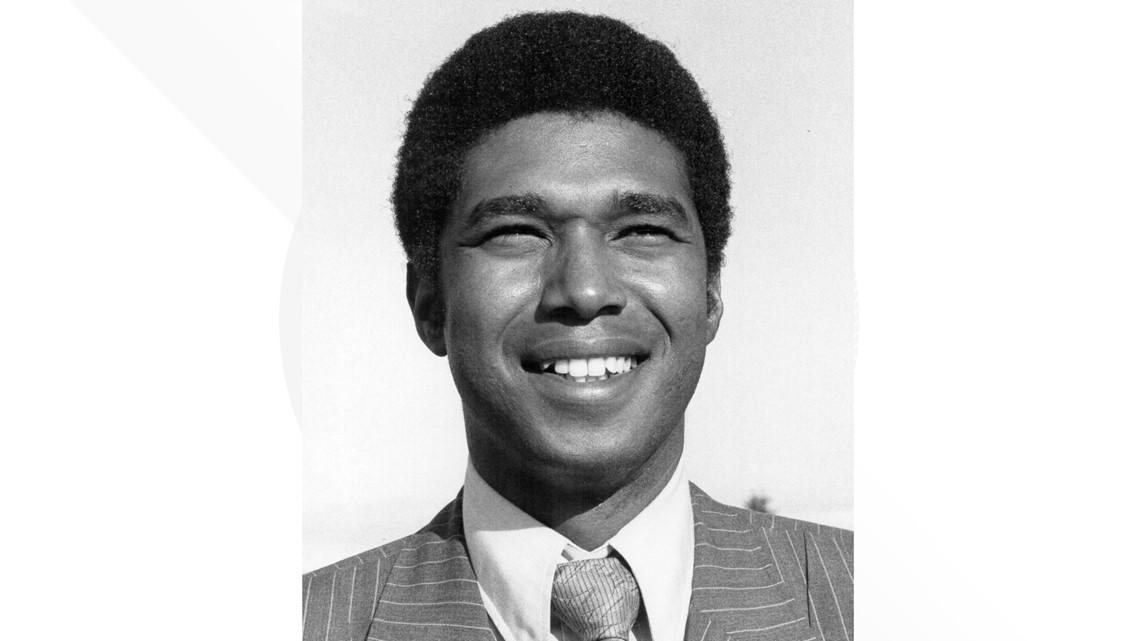

At 80 years old, Pointer is living perhaps better than he was at 20 years old.

"I was the only Black player playing on the team in Salisbury [North Carolina], which was absolutely terrible," Pointer said.

This was in 1961.

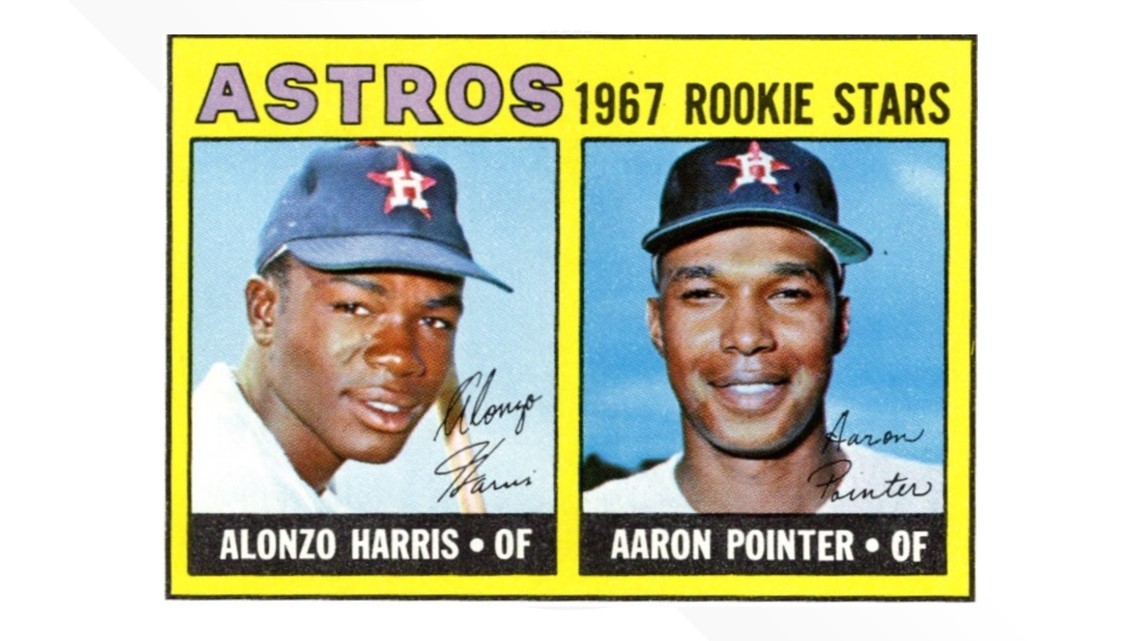

"I signed a pro baseball contract with the Houston Astros," said Pointer, who was subsequently assigned to the minor league Salisbury Braves. "They were going to be a new team in the National League. I did it for the money. We grew up in a poor neighborhood and we didn't have much money ... (I) had never heard of Salisbury, had never been to North Carolina ... I was from Oakland and had never seen the prejudice and racism that I experienced in Salisbury. It was just unique to me."

It was this racism that led to the Civil Rights Movement.

Pointer said he witnessed firsthand activists like the Freedom Riders and John Lewis, who had come to Salisbury to promote voter registration.

Yet those sentiments didn't register with the rest of the town.

"(The) bus would stop at restaurants and (my teammates) would go eat dinner and I couldn't go in any of the places and eat," Pointer said. "(I) had to go in the back door to see the doctor, the team doctor - couldn't go in the front door. I was an outfielder and there was a kid in the outfield who was shooting BBs at me with a BB-gun ... (There were) newspaper articles that were complaining about me being on the team and that I was showering with the white players."

For Pointer, it was a season of struggle, yet somehow, a season of success as well. It was a season when he found a safe space.

"I could've stayed at the ballpark 24 hours a day if it was up to me and lived there," Pointer said.

Instead, Pointer lived in the minds of opposing pitchers.

He started his first pro season with 40 hits in 73 at bats.

"When I was playing ball, I was just playing ball," Pointer said. "I wasn't worried about all the other stuff."

By the end of the year, the magic number was within reach. Pointer recalls a conversation with his coach before the last game of the season.

"He asked me if I wanted to play or not and I said, 'Why what do you mean if I want to play?'" Pointer said. "He said, 'You know you're hitting .401.' I said, 'So what? Sure I want to play.' I played in the game and went 2-for-3 and ended up hitting .402 for the season."

Pointer said he thinks his historic season will stand the test of time.

But he'd rather the memories suffer a different fate.

"I've never been back to Salisbury," Pointer said. "I don't have any intentions to go back to Salisbury."

While the memories were sometimes beautiful, they're memories he'd rather bury completely.

"It really takes its toll on you," Pointer said. "It's something that you know it's there, but you don't want to talk about it because it's just too much of a distraction and too hurtful to talk about."

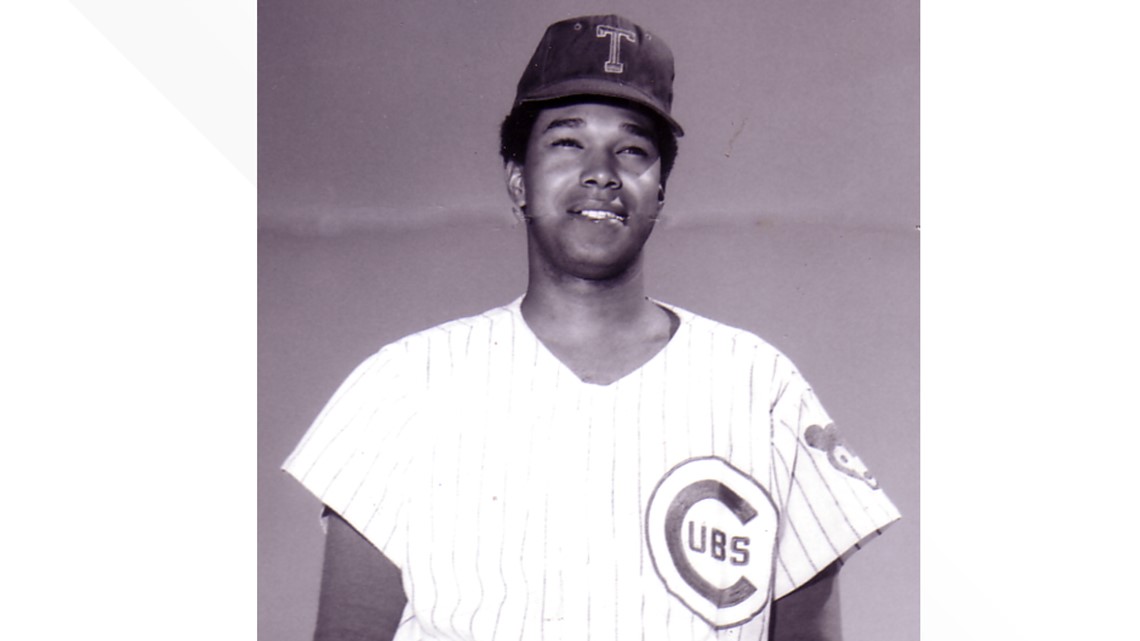

Pointer was traded to the Chicago Cubs in 1968 after an incident with his teammate, Rusty Staub.

He played with their Triple-A affiliate, the Tacoma Cubs, for two seasons.

Pointer has spent the rest of his life in Tacoma and is on the board of the Tacoma Athletic Commission.

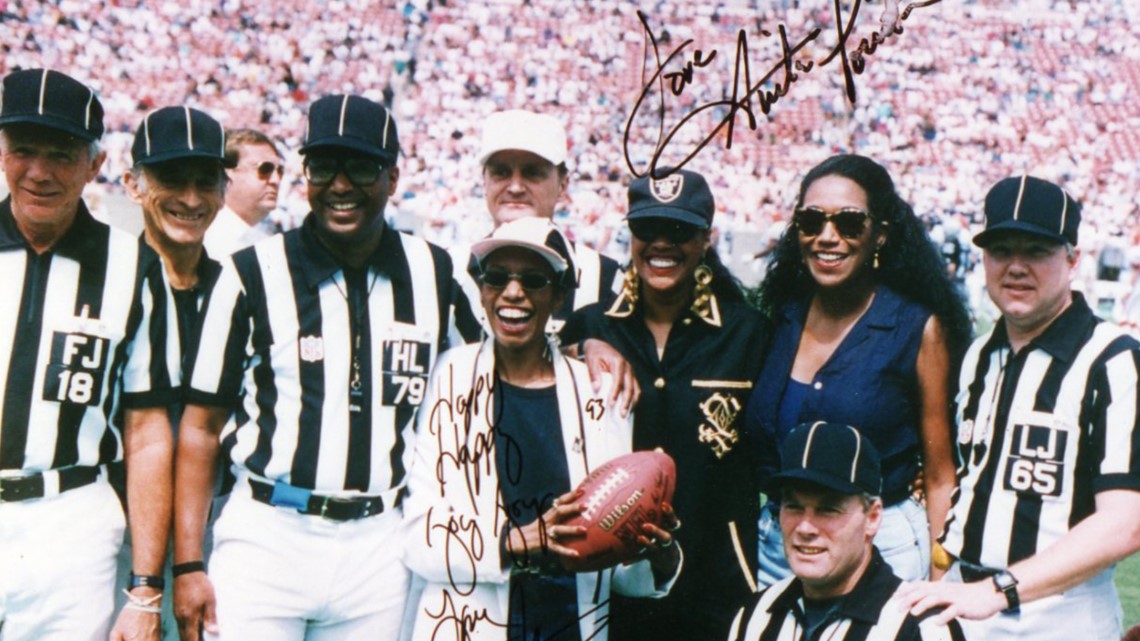

He's a former NCAA and NFL referee and is the older brother of the Grammy-winning The Pointer Sisters.