MEDICAL LAKE, Wash. — Life is returning to Medical Lake.

Friday, the air was filled with the sounds of construction as house after house is rebuilt. Hammers laid on new siding, saws cut new framing, and roofers scaled back and forth on new homes taking shape. The sights and sounds were all welcomed by John Altheide.

"It's exciting," he said with a smile. "It's our community coming back, which is what we wanted to see."

He's rebuilding his home and the life he and his wife started here five years ago when they bought some land and built a brand new home. That home burned to the ground during the August 18 Gray Fire.

Altheide said they were lucky the home was so new. The builder still had the plans and they'd kept up on inflated costs to rebuild through insurance, meaning within a week, they were breaking new ground to replace the unique home exactly as it was.

He knows he's in a better position than many of his neighbors.

"Most of us were like, 'what do we do? What do we do?'" he said of the moments after the fire. "All we knew was maybe call our insurance."

It's that confusion and the lack of immediate assistance from the state and federal government that have plagued wildfire victims in Medical Lake and in Elk where the Oregon Road fire hit the same day, slowing the recovery and rebuild process.

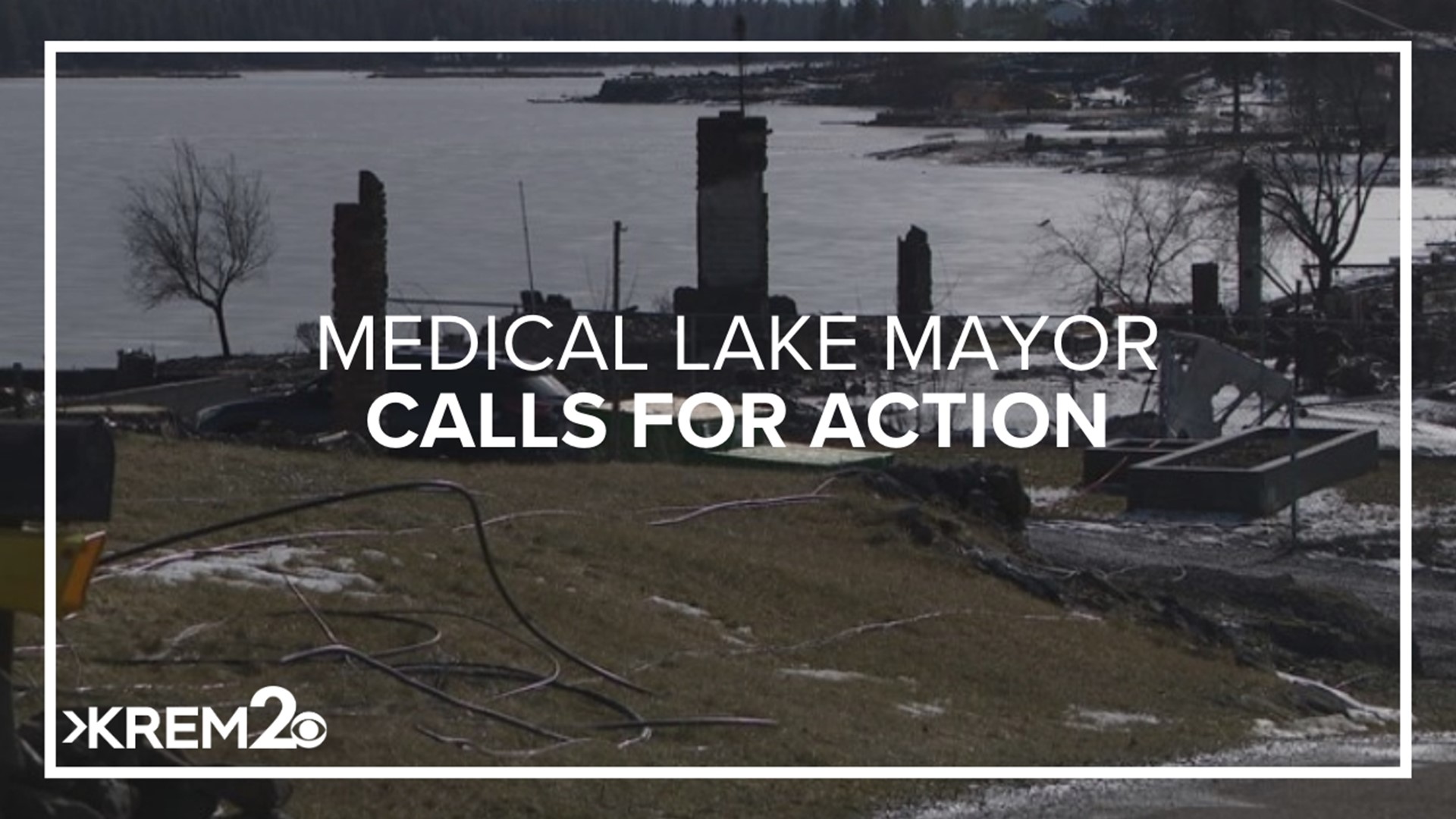

On the west banks of Silver Lake, that slow progress is more visible, with many burned plots still untouched.

Medical Lake Mayor Terri Cooper says it's a sign of how slow recovery can be.

"Probably 150 homes along this west shore that were destroyed," she said.

Though Cooper would says the slow recovery evidenced here shouldn't be, not in a state like Washington so accustomed to wildfires.

It's a problem she's fighting to change forever.

"That we could deploy a team and it wouldn't take months and months to set up these groups and get things going," she said of her proposal, now working its way through the statehouse.

Cooper helped initiate and has vocally advocated for a bill in Washington's legislature that would establish a statewide long-term disaster recovery program. If passed into law, it would require the state's military department to establish the program to assist county and tribal governments with long-term community recovery planning. That includes developing and updating a manual for long-term community recovery, issuing grants to assist with creating and running long-term community recovery groups across the state, providing training, and creating and updating a resource directory of state, federal, and international agencies and resources.

Soon after the Gray Fire, residents like Altheide turned to one another to figure out where to go for services and help.

"Got information and started passing it along. We found out about asbestos testing and I had a list of 27 numbers someone gave me," Altheide said.

He only figured out which excavating service to contact by noticing which one was parked outside a neighbor's home.

Cooper says those closest to the community are best suited to know what resources are available in an emergency, so she wants this program to centralize all resources through various nonprofits and agencies, creating a deployable team and a disaster reserve fund in the governor's budget.

"Even here in Medical Lake we had to spend money we hadn't allocated," she said of the costs of recovery.

When asked about how much it has cost to clean up, she said it's almost unquantifiable, especially since so many homeowners have been saddled with paying for the various expenses themselves. Asbestos testing, for example, averages around $3,500 and is often on the property owner to pay. If a site tests 'hot' for asbestos, clean-up can run anywhere from $60,000 to $80,000, Cooper has explained.

Cooper wants a statewide recovery program that would get money and boots on the ground even faster.

"The very next day that group would meet and they would get all their partners together and they'd start talking immediate needs, long-term needs, case managers on board within days, not months," she said.

The delays in recovery and rebuilding carry more concerns than just returning residents to life on the lakeside. The toxic debris carries toxic chemicals which, after sitting for more than five months, are now migrating according to Cooper.

"Soon as it starts raining, soon as there's snow on the ground it's leaching into the soil, it's running off into our lakes," she said.

She says those chemicals are likely making their way into aquifers and into the Spokane River, only passing the problem to other communities and the ecosystem. The delay in mitigating those long-term risks are just another reason she wants to see this first-of-its-kind program come to life.

"The faster you can get the dollars to the community and the closer you can get it to where the highest impact happens," she said.

Cooper believes this would be a "game-changer" for communities across the state. The bill recently passed out of committee well before the deadline, now making its way to both chambers of Washington's legislature.

"We're hoping we'll get unanimous approval all the way through," Cooper said. "I'm hopeful."

DOWNLOAD THE KREM SMARTPHONE APP

DOWNLOAD FOR IPHONE HERE | DOWNLOAD FOR ANDROID HERE

HOW TO ADD THE KREM+ APP TO YOUR STREAMING DEVICE

ROKU: add the channel from the ROKU store or by searching for KREM in the Channel Store.

Fire TV: search for "KREM" to find the free app to add to your account. Another option for Fire TV is to have the app delivered directly to your Fire TV through Amazon.

To report a typo or grammatical error, please email webspokane@krem.com.