SPOKANE, Wash. — In his west Spokane pastures, Craig Volosing's personal paradise is contained.

"I think these horses may be just too curious. They’re really friendly," he said, locking a gate to the area where he keeps boarded horses.

As a boy, Palisades Park lived in his back window until he found a life here in 1976.

"Always wanted to be with horses so this was the place for me," he said of his home in the tree-covered rural area adjacent to the park.

It was a peaceful haven until 2017.

That's when per and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, known as PFAS, were detected in Airway Heights water and private wells; it was traced back to firefighting foam used at Fairchild Airforce Base.

The same foam, Volosing knew, was also used at Spokane International Airport (SIA) just miles southwest of his home.

"In 2018 we had our well tested out here and it was negative, but I told my wife, ‘It’s coming,'" he recalls. "And it did.”

Up until early this year it was believed the PFAS problem only impacted people west of the arbitrary boundary of Hayford Road. People on the Airway Heights side were given bottled water and well testing almost immediately after the city and AFB discovered the contamination.

But as concerned neighbors later dug up, the airport on the opposite side was testing its own wells and finding a similar issue.

"Found they had PFAS. And plenty of it. And chose to say nothing," Volosing said.

Citizen-initiated public records requests turned up the airport’s own test results from 2017 and 2019 showing the contamination. KREM 2 News spoke to the Palisades resident who initiated the records request that unearthed the contamination; that person did not want to speak on camera.

Though Volosing says he and other neighbors who understand the hydrogeology of the area and were concerned about the possibility of PFAS spreading helped push for more answers, including why grant money wasn't being sought to remedy the chemical spread.

PFAS weren’t listed as hazardous, and thus state-regulated, until 2021. That’s when SIA had a legal responsibility to report the findings. It didn’t.

"Should have," said Nicholas Acklam, the eastern Washington section manager for the Department of Ecology's toxics cleanup program. "No, we didn’t know until it was, like you said, reported by a concerned citizen in 2023.”

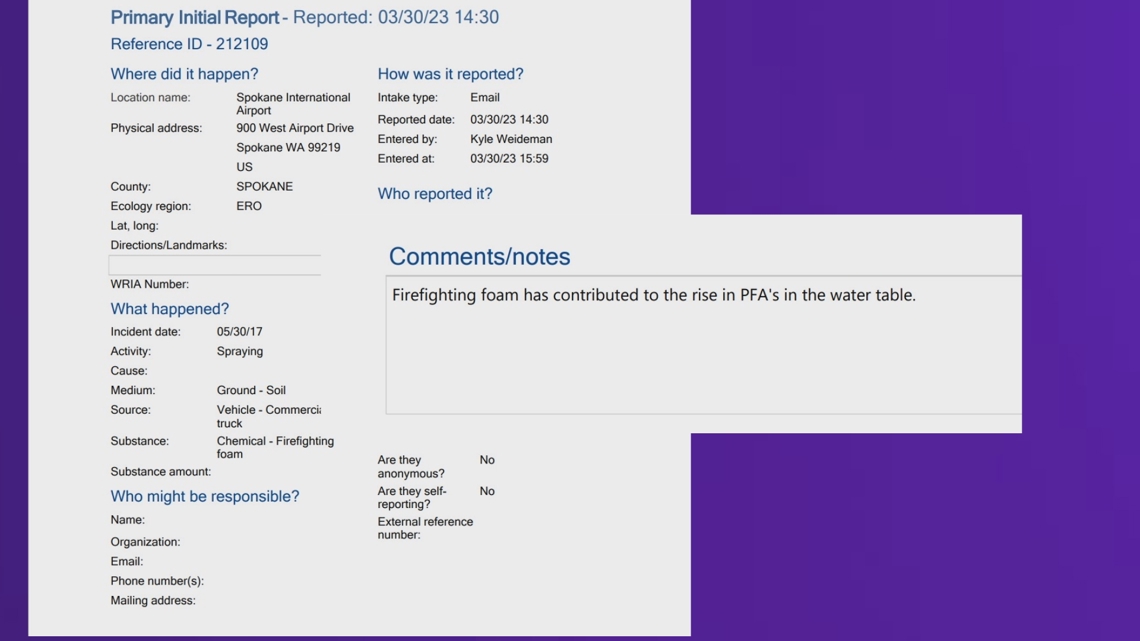

A complaint made in March 2023 to Washington's Department of Ecology shows a concern that firefighting spray at the airport had 'contributed to rising PFAS levels on the water table.'

The department, in partnership with the EPA, has since tested 411 wells east of Hayford Road, in a sampling priority area believed to be contaminated by the airport site.

"About 65% of those had concentrations above our action levels," Acklam said. "That’s a lot. Yeah, it’s a significant number and we’re working as fast as we can.”

"But we are seven years behind," Volosing exclaimed. "This could’ve started back in 2017, 2018 but didn’t. And the question remains just why.”

Airport leadership declined KREM 2's interview requests, saying it is in “full compliance with the Department of Ecology’s order.”

An August site assessment identified around a dozen points where firefighting foam was used or stored. Working under an enforcement order, SIA must sample the dirt and groundwater at each site before any clean up can begin.

"Average is about 12 years," Acklam said of site cleanups. "But that’s average, this is a pretty complex site so it certainly could take longer.”

Ecology is still trying to determine the true scope and scale of contamination near the airport and where the chemicals have traveled.

"So that’s really the first step. It’s really hard to design a feasibility study until you know the full extent of where your contamination is," Acklam said.

Volosing’s well tested PFAS-positive early this year.

Inside his old pumphouse, fresh drinking water used to be a source of pride. It's now been replaced with bottled jugs.

"Provided to us happily by the Department of Ecology and EPA as a stopgap," he said.

Though the well still flows to their greenhouse and livestock. Volosing says the cattle they raise for customers has, so far, tested negative. Though he’s curious how these chemicals may be impacting other lives in his paradise. He's waiting on testing he can afford for his horses to see if they have PFAS in their systems.

"Good, good," he said, stroking his horse, Dante. "You’re a good boy.”

For now, he's also awaiting action from the airport and Spokane County's board of commissioners, where he also places some of the blame for the slow response.

"That decision, not to let the public know or the authorities know, the Department of Ecology, cost us seven years. And that's the biggest problem," he said. "It's one thing to have your water source polluted. To keep it from the public is unconscionable, it destroys your trust."

SIA has announced its CEO, Larry Krauter, is departing after 14 years leading the airport; Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport announced he will take over as CEO in 2025.