From Tennessee to Oregon: How lawyers turned the ADA into a ‘shakedown business model’

A Tennessee law firm paid people with disabilities to visit targeted businesses, then sent demand letters threatening to sue the owner if they did not comply.

Conner Slevin got an unexpected message on Facebook in June of 2022. A man in Texas, who shares mutual friends, reached out with an offer. He encouraged Slevin to help with a project aimed at making businesses more accessible for people with disabilities.

“This seemed like an opportunity to do something good,” said Slevin, 34, who was paralyzed from the shoulders down in a beach accident in 2020.

The Facebook message explained that each month, a lawyer would provide Slevin with a list of two or three businesses in the Portland area. Slevin would have to visit each location, take a couple photos and buy a Coke or some other inexpensive item. In exchange, the out-of-state lawyer would pay Slevin $200 per visit.

Slevin, who lives in Northeast Portland, had questions about the operation. He also found it odd that many of the businesses he was sent to appeared to be owned or operated by minorities.

“I was starting to put together the pieces,” Slevin said.

In May, a KGW investigation confirmed his suspicions. He quit the operation and asked to no longer be associated with the lawyers who sent dozens of demand letters to small businesses in the Portland-area threatening to sue if they didn’t bring their property into compliance with the ADA and pay attorney fees of roughly $10,000.

A disproportionate number of the ADA lawsuits — about half — involved Asian-owned businesses, according to court records, state filings and interviews.

“I realized that these people are not representing me in a way that I agree with,” said Slevin. “I’m a tool in their operation.”

Over the past three months, KGW has spoken with more than 40 people directly involved with or targeted by the operation run out of the Tennessee law firm Wampler, Carroll, Wilson & Sanderson.

The Wampler firm, along with attorney B.J. Wade of Memphis, follow a playbook. They find people with disabilities willing to visit businesses to help identify ADA violations. Then, they hire a local lawyer who sends the business a letter threatening to sue and attaching a boilerplate complaint. The demand letter offers an alternative, if the property owner pays roughly $10,000 in “lieu of attorney’s fees” and brings its property into ADA compliance, the lawyer won’t sue the business.

“We have pursued over 4,000 of these cases across the country and in 90% of cases, we have been successful in requiring the property owners to get in compliance with the ADA,” B.J. Wade wrote in a text message to Slevin on June 3.

If that number is correct, a settlement of $10,000 in 4,000 cases would generate $40 million in attorney fees. Even if the settlement amounts were less, the attorneys would still pocket millions.

Wade did not respond to KGW’s request for comment for this story.

“It’s a business model. It’s a shakedown business model,” said attorney Ken Burger, who is defending an ADA case against the Wampler firm in Tennessee. “These attorneys are working off the backs of disabled souls who have enough problems in their lives. They’re being exploited.”

Recruiting people with disabilities $200 per visit to businesses

Justin Burley Beavers lost his legs at ten months due to meningococcal meningitis. The 26-year-old double amputee uses a skateboard to get around his apartment complex in Southeast Portland. He plays sports, so it was no surprise when someone in the wheelchair rugby community reached out on Facebook. The man suggested a lawyer was willing to pay $200 per visit if Beavers would go to local businesses and take a few photos.

“The Tennessee law firm was telling me they needed representatives in Oregon,” Beavers explained.

Beavers estimates he’s visited more than 60 locations over the past two years.

“They give me a specific spot. I go there. I take my pictures. That’s it,” said Beavers.

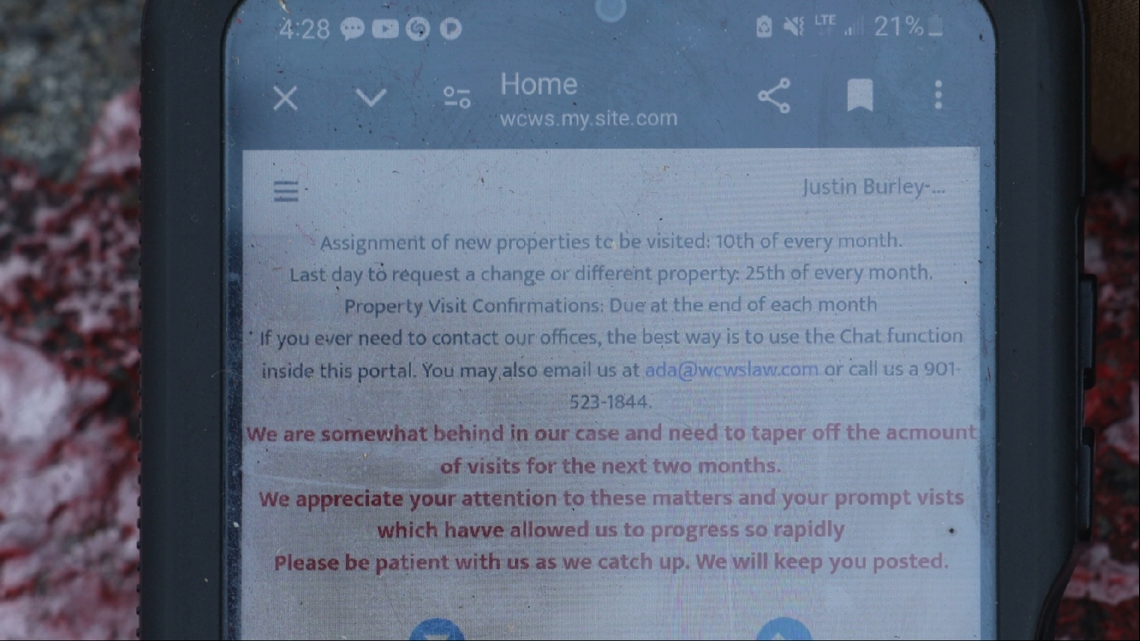

The Wampler firm initially had people with disabilities email their photos confirming each visit. Now, the operation uses an online portal, hosted on the Wampler firm website, where users log in with a name and password.

“Assignment of new properties to be visited: 10th of every month,” the portal reads along with directions, a chat feature, email and phone number connected to the Wampler firm. The website also lists dates of assignment, dates of visit and any notes.

As Beavers scrolled through the website, a list of past visits displayed on his phone. On January 20, he went to a Thai restaurant on Southeast Belmont. On March 18, he visited a Plaid Pantry on Southeast McLoughlin. On June 21, Beavers visited a strip mall and nail salon on Southwest Canyon Road in Beaverton. The nail salon is an hour-and-a-half bus ride from Beavers’ Southeast Portland apartment.

The website showed Beavers visited 37 locations since August 2023. Many of the restaurants and convenience stores were never named in lawsuits, suggesting they settled out-of-court by paying the attorney fees and making fixes to be ADA compliant. Beavers said he never went back to check and see if the repairs were made.

Beavers admitted, most of the locations were not places he’d visited before or planned to return to, and he didn’t know who was creating the list.

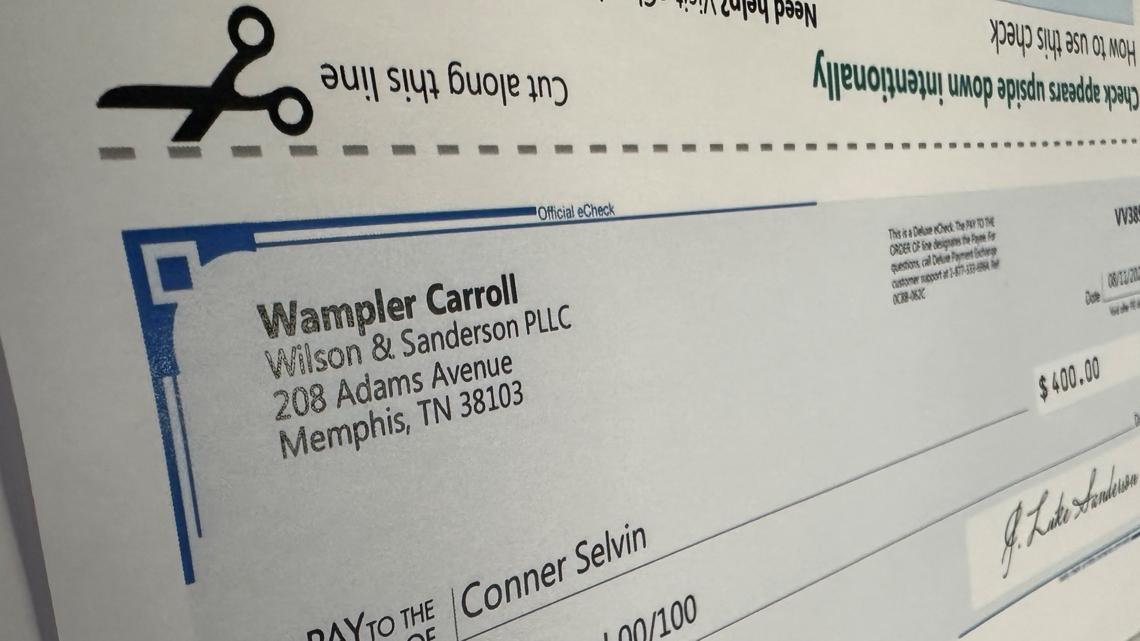

“It’s two to five places a month. $200 per place,” Beavers explained. “Then, they send me a check after I visit each place.”

The checks from “Wampler, Carroll, Wilson and Sanderson” are delivered electronically. The memo describes them as ‘Expense Reimbursement” and they’re digitally signed by attorney J. Luke Sanderson of the Wampler firm.

“This isn’t about money,” Beavers explained. “This is about making everything accessible for everyone.”

The Americans with Disabilities Act Making businesses accessible

The ADA is the 1990 federal law that protects the rights of people with disabilities. Title III of the ADA requires that all businesses open to the public must be accessible — meaning they must provide people with disabilities an equal opportunity to access the goods or services they offer. If businesses don’t comply, they can be sued without warning.

New construction must be built according to the ADA’s standards. Buildings constructed before 1991 must remove existing barriers when it would be readily achievable.

The federal law prevents individual plaintiffs from collecting monetary damages. A successful ADA lawsuit generally ends in injunctive relief or a judge ordering the violation to be fixed and the plaintiff’s legal fees to be paid by the defendant. Because the law requires defendants to cover legal fees, it can incentivize lawyers to sue or drag the case on.

Conner Slevin thought his attorneys would use the ADA to improve accessibility. Instead, he finds himself trying to untangle the legal mess they helped create.

In a lawsuit filed earlier this week, Slevin sued his former attorney Jessica Molligan for legal malpractice.

The Portland lawyers 50 small businesses sued

Molligan and another Portland lawyer, David Foster have sued roughly 50 small businesses in the Portland-area since the fall of 2023 on behalf of three separate clients Conner Slevin, Justin Burley Beavers and Nadia Roberts. Following KGW’s investigation, Foster admitted he was hired as local counsel by the Wampler firm of Tennessee and resigned from the cases — transferring them all to Molligan.

It's not clear how many demand letters Molligan sent to Portland-area businesses. Many property owners said they were told to keep things secret and court records prove it.

A settlement agreement with Molligan shows that details about terms, conditions, and payments are to remain “strictly confidential.” The secret paperwork only became public after Molligan sued a property owner that didn’t pay her $6,000 in attorney’s fees.

“It’s affected me, and especially my family. I don’t want this happening to anyone else.”” said Peter Lee, son of Abraham Lee who owns a commercial building on Northeast Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard.

Lee, who is a lawyer in Washington state said Molligan didn’t dismiss the lawsuit against his father within five days of signing the settlement, as agreed upon by the parties.

“She emailed maybe a month later saying she forgot but still wanted to get payment and would sue us for payment,” Lee explained.

Lee claimed there have been several questionable legal actions taken by Molligan, including calling his father directly. Ethics rules prohibit lawyers from speaking with parties represented by counsel.

One of the property owners Molligan sued for ADA violations filed a motion in federal court seeking sanctions. The motion claims Molligan abused the court process and violated state ethics rules. “Counsel appears to have participated in an unethical compensation scheme,” alleged attorney Iain M.R. Armstrong, who represents a small, family-owned strip mall on Northeast Sandy Boulevard.

In a separate case, filed in state court, a property owner sued by Molligan filed a lawsuit accusing the attorney of breach of contract and fraudulent misrepresentation.

Molligan had her law license suspended for 120 days in 2021 after she failed to keep her client informed about the status of a case. A spokesperson for the Oregon State Bar said it received two complaints stemming from Molligan’s ADA demand letters and lawsuits.

Molligan declined to comment after leaving the federal courthouse in downtown Portland last week. During a hearing, Slevin asked a judge to dismiss his pending lawsuit against a Portland property owner and no longer have Molligan on the case.

“I’m trying to wash my hands of this whole situation,” Slevin told the judge who granted his request.

Boilerplate lawsuits filed in multiple states 'Taking advantage of an unfortunate situation'

The lawsuits filed by Molligan in Oregon are nearly identical to those filed by the Wampler firm in Tennessee.

According to court records, attorneys at the Wampler firm have filed more than 100 federal ADA lawsuits in the Middle District of Tennessee since 2019.

Burger, the Tennessee attorney defending one of those lawsuits, questions the Wampler firm’s pattern of behavior.

“It’s the up front shake down of attorney fees that I think is an unethical business model,” said Burger.

In January, Chief U.S. District Judge Waverly Crenshaw, Jr. of the Middle District of Tennessee warned a lawyer from the Wampler firm to proceed with caution.

“This conduct raises serious ethical issues under the Tennessee Rules of Professional Conduct and the intentions of the ADA’s civil suit provision,” wrote Judge Crenshaw. “Courts across the country have condemned this shakedown-like behavior.”

KGW has been seeking comments from the Wampler firm by phone and email since June. The lawyers have not responded.

In addition to the cases in Tennessee, KGW’s review of federal court records identified lawsuits in several other states matching the Wampler firm’s template. ADA lawsuits filed in Arkansas, Maryland, Oklahoma, North Carolina, Texas and Alabama include the same language, punctuation, indentation and format.

“It’s cookie cutter,” said Slevin. “Lawyers taking advantage of an unfortunate situation. Taking advantage of vulnerable communities all along the way for their own profit.”