An investigation into the death of a University of Utah student shot by a man she briefly dated found her friends had reported his controlling behavior and interest in getting her a gun nearly a month before the shooting, but that warning never made it to police.

The probe released Wednesday also shows that university detectives looking into a subsequent harassment report from 21-year-old student Lauren McCluskey did not discover he was a sex offender who had been released from prison months before.

University President Ruth Watkins said the institution is “acting on every single recommendation” in the report by university and state officials. But she maintained that nothing in the review indicated McCluskey’s death could have been prevented.

“Instead, the report offers weaknesses, identifies issues and provides us with a road map for strengthening security on our campus,” she said. She denounced 37-year-old Melvin Rowland as a “manipulative, evil criminal” who “exploited vulnerabilities” in the system.

The probe also shows campus police are overtaxed and need more training in handling domestic violence cases.

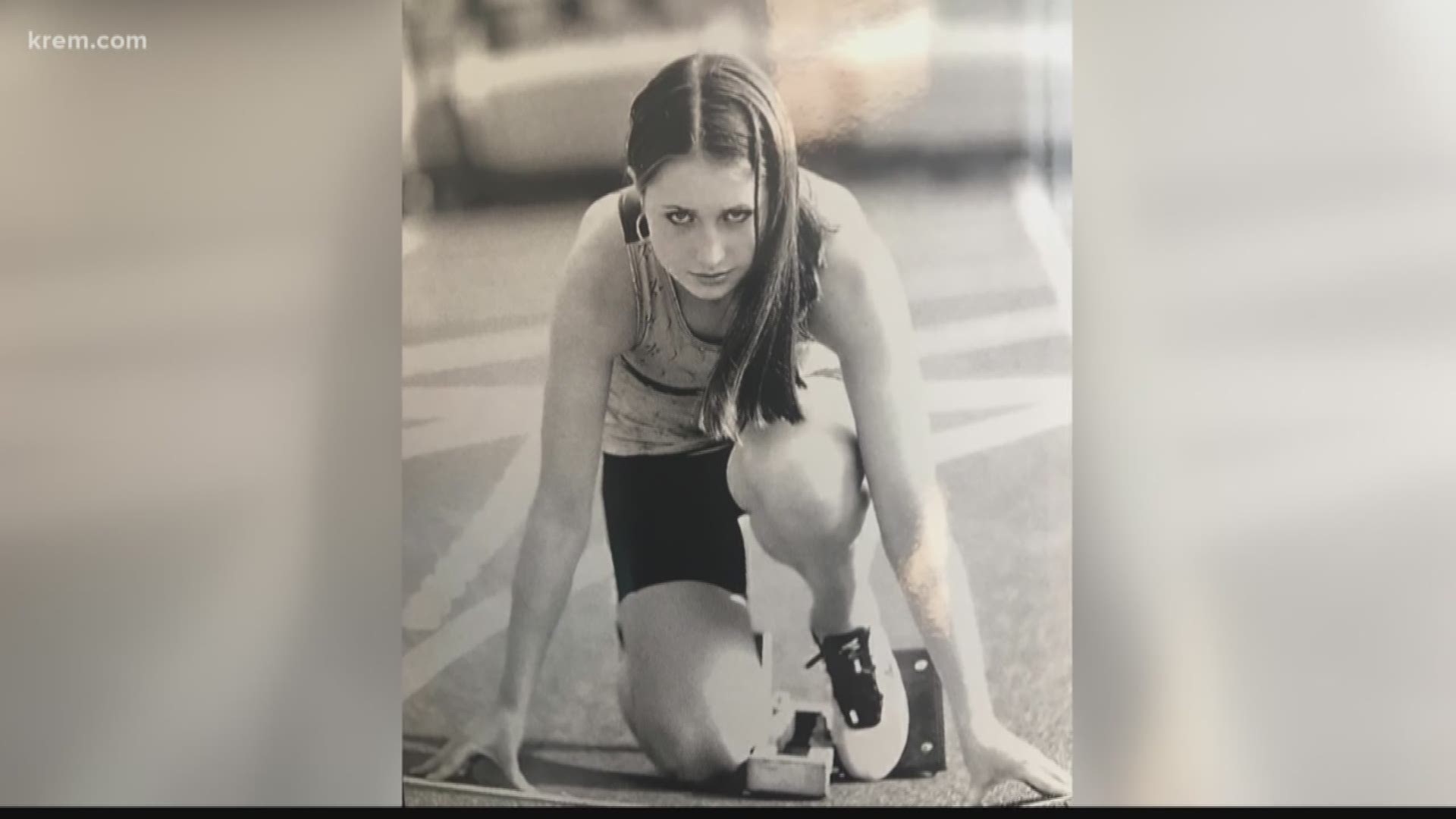

McCluskey, a track athlete and communications major, was fatally shot by Rowland on Oct. 22, after she dumped him because he had been lying about his identity, criminal history and age. Rowland killed himself as police closed in.

More than a week before her death, McCluskey had reported to police that her ex-boyfriend was harassing her and demanding money in exchange for not posting compromising photos of her online. Police investigated, but they never checked him against state records where they could have discovered he was a parolee.

Running those checks wasn’t required or typically done under university police policy, something the institution is now changing. Even if they had discovered he was an ex-convict, it’s not clear whether the harassment complaint would have been enough to send him back to prison because he had appeared to be meeting the conditions of his parole otherwise, Utah Public Safety Commissioner Jess Anderson said.

Still, McCluskey’s friends had long been concerned about the relationship. In late September, they told a residence-hall official that she was in “an unhealthy relationship with an older man who was controlling her,” the report states. He’d also said he wanted to bring a gun on campus to give to McCluskey, which could have been a violation of his parole if authorities had discovered he was an ex-convict.

Bureaucratic snafus kept housing officials from submitting the report, and concerned about overstepping into McCluskey’s private life they ultimately decided to monitor the situation. The university should make it simpler to make such reports and involve victim advocates sooner, said John Nielsen, a former commissioner for public safety.

Likewise, the detective investigating McCluskey’s harassment complaint didn’t have the training or experience to recognize the signs of domestic violence in her relationship, the report found. The university plans to do more training, as well as request funding for five more officers to ease the workload on the department.

The case also exposes weaknesses in the state’s parole system, Anderson said. Rowland, for example, was in the system under a state identification number rather than his driver’s license, so when university police ran his license it didn’t flag his criminal history. He had also been using aliases to circumvent rules against him being on social media, unbeknownst to the state.

After a separate review ordered by the governor, Anderson is recommending updating and simplifying the systems designed to track ex-convicts and alert agents when one crosses police radar.