WELLPINIT, Wash. — The concept of environmental racism emerged from the environmental movement of the 70s and 80s, but was a lived experience for communities of color long before that, and one too many continue to suffer today.

A consequence of systemic racism, it’s the disproportionate burden of environmental impacts on Black, indigenous and people of color groups, according to Isabel Carrera Zamanillo, diversity and inclusion program specialist at the University of Washington College of the Environment. That can mean proximity to pollution, unfair policies or limited access to natural resources.

The Spokane Tribe’s experience with the legacy of uranium mining on their Eastern Washington reservation is an illustration of environmental racism. The reservation was established in 1881, and the tribe lived in region long before.

But in the atomic sprint of the Cold War, rich deposits of uranium were discovered on the land, and the Midnite Mine opened to extract it. It finally closed in 1981, leaving behind two open pits and slew of hazardous environmental problems: toxins leaching into the groundwater, soil and air, as well as a risk of human exposure to contaminants.

“They found [uranium] on Indian land, and it was opened up for companies to come in and pay minimal for the resources,” said Twa-le Abrahamson-Swan, an environmental activist and member of the Spokane Tribe.

Compounding the issue for the tribe is the fact that they were relegated to the Selkirk Mountains in the first place by white people moving West. The tribe's history describes ancestors as "living a semi-nomadic way of life hunting, fishing, and gathering all creator had made available to them" along the banks of the Spokane and Columbia rivers and tributaries.

“When allotments were being made, our people were pushed to the mountain areas, because at that time a lot of the farmlands were more desirable,” Abrahamson-Swan said.

But in the race for the bomb, uranium was too valuable to ignore, and early mines operated with relatively relaxed safety oversights by modern standards.

WATCH: Full episodes of Facing Race

Four decades later, Abrahamson-Swan’s fight continues to get the reservation cleaned up.

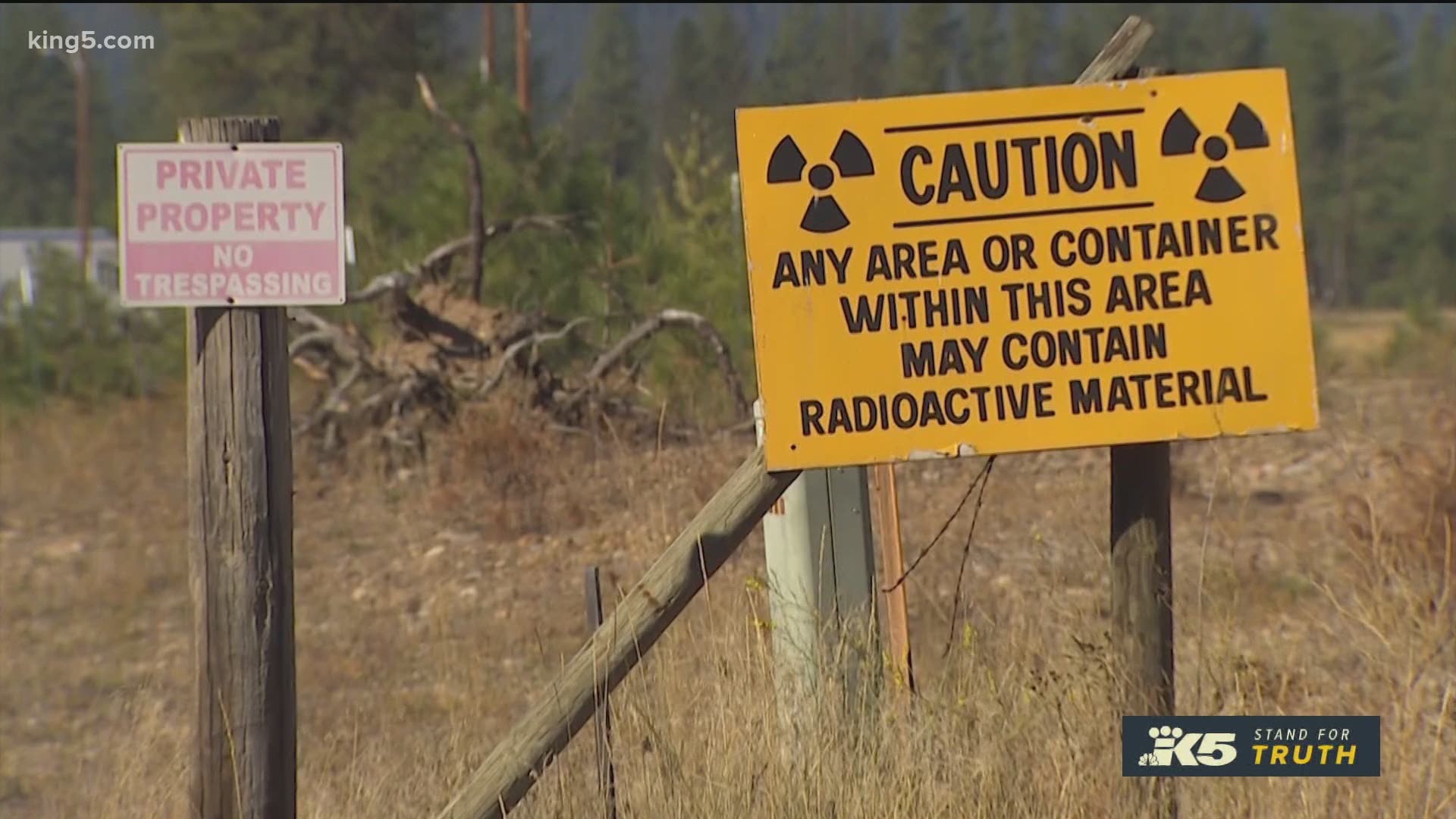

At the edge of the reservation, the mill processing facility has been demolished, though signs warn of radioactive danger along a barbed wire fence. The Washington Department of Health is responsible for cleanup here and writes, "Ongoing cleanup activities involve completing soil cleanup, evaporating remaining process water, and addressing contaminated ground water."

And a few miles away, the Midnite Mine sits upstream of Blue Creek, which marked with signs warning plants and animals may not be safe for human consumption. The mine is now an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Superfund cleanup site after the federal government sued Newmont Mining, which owns Dawn Mining, to bring them back for cleanup.

“In addition to elevated levels of radioactivity, heavy metals mobilized in acid mine drainage pose a potential threat to human health and the environment,” the EPA writes.

“It’s contamination that you really can’t see or smell,” Abrahamson-Swan said. “So they could be going generations and generations drinking the water, breathing contaminated air and not knowing it.”

The EPA site has a laundry list of chemicals found in the air, soil and water – lead, radium, radon and uranium to name a few. The EPA lists human exposure and groundwater migration as not under control at the site.

“In combination, what do all these as a mixture do to the human body?” Abrahamson-Swan said. “And it’s not studied.”

She noted a cluster of rare health problems cropping up among tribal members, which she tied to the contamination.

“In a series of meetings a couple of years ago, we had a span of about three months and we lost 10 tribal members to cancer during that time,” Abrahamson-Swan said. “And it was an eye opener.”

But Abrahamson-Swan said the tribe has struggled to get health studies done on the population there.

The issue of uranium mining on reservation lands extends beyond the Spokane Tribe. A 2015 paper in the journal “Geosciences,” notes a “legacy of long-lived health effects for many Native Americans and Alaska Natives in the United States.”

But the fallout of environmental racism is more than a concept for Abrahamson-Swan. Her mother, activist Deb Abrahamson, was diagnosed with terminal cancer in 2016, a disease she ties to the mine.

“It angers me,” said Abrahamson. “It angers me that I’m in this situation, and it was preventable in a sense of earlier detection and being able to do things in a different way.”

Asked what she believes is the core issue at work in this situation, Abrahamson didn’t mince words.

“Racism is one of the biggest,” she said after a pause. “Because when our country was invaded, we were viewed as a dispensable population, subhuman. So it was easy to be able to do the level of damage that has occurred on tribal lands because the people are viewed as subhuman, and have no rights and no say in how we conduct our lives.”

Asked for comment about health impacts, Newmont Mining sent the following statement:

“Newmont/Dawn have no information that any tribal member’s health has been impacted by the mine. All employees at the site participate in a comprehensive health and safety program to ensure safe working conditions are maintained and that no contamination leaves the site. Similarly, exposure levels are regularly monitored and reported to authorities.”

On solutions, Zamanillo said fighting environmental racism requires we all consider the impacts of products we buy and consume – where materials are mined and how it’s shipped. But she also notes we must continually include impacted communities in the solutions.

“First thing we need to consider is what each community considers sacred, and what is their interest,” she said. “It’s not just about solving problems, but also listening these communities and collaborating.”

That’s been Abrahamson-Swan’s experience.

“I think what we see are decisions made on behalf of the community are at the root of some of the problems,” she said. “Because when you don’t have the impacted community in the room at all levels, these are are the people that are going to have to live with this decision for our entire lives.”

Now, Abrahamson-Swan and her mother are pushing for better community health monitoring and funding for a clinic for the Spokane people. They hope with earlier detection and continuing cleanup, they can move past life as a uranium impacted community.

“The land is beautiful,” Abrahamson said. “There’s people all over it. It looks so wonderful. Yet when you look underneath, it’s a deadly, toxic slime that isn’t going to go away. And it’s stuck on our people.”

This story was produced as part of “Facing Race,” a KING 5 series that examines racism, social justice and racial inequality in the Pacific Northwest. Tune in to KING 5 on Sundays at 9:30 p.m. to watch live and catch up on our coverage here.