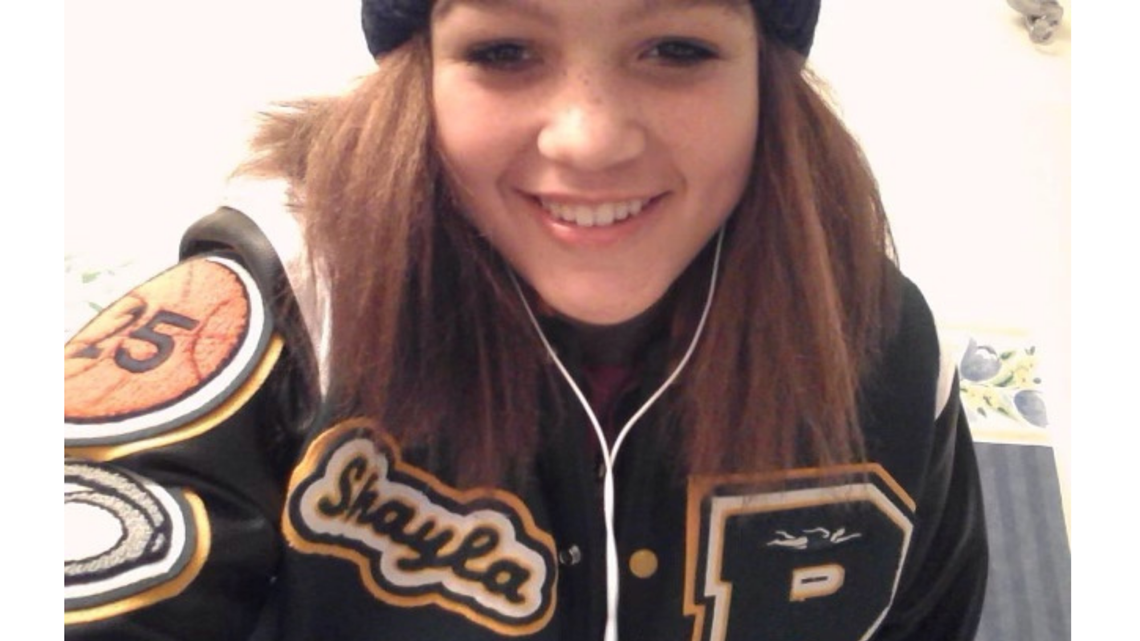

Enough: George Floyd's biracial cousin finds her place in the fight for racial justice

To Shayla Zartman, George Floyd was simply "Perry," one of her cousins on her family’s Black side. His death fueled her own racial reckoning.

Taylor Mirfendereski / KING 5

Reckoning

Shayla Zartman woke up early on May 26, relieved she was finally feeling better after a virus had her stomach twisted in knots for days.

Morning light illuminated her spacious college apartment at Central Washington University in Ellensburg, where she was a freshman. She untangled herself from her sheets and grabbed her phone from the charger. She noticed two text messages from her older half-brother, Sean York.

The first included a link to a news article with the headline, “Video shows Minneapolis cop with knee on neck of motionless, moaning man who later died.”

In the second, Sean warned his sister not to watch the video accompanying the story.

He didn’t say why.

Shayla had questions after reading the article, which detailed how a Black man died outside of a corner store, gasping for air with his face wedged for nearly nine minutes between a city street and a white police officer’s knee. She turned to Twitter for answers.

Video clips of the man moaning “I can’t breathe,” began to autoplay as Shayla scrolled through trending hashtags: #BlackLivesMatter #ICantBreathe, #JusticeforFloyd, #GeorgeFloyd.

George Floyd was becoming a household name and a focus of viral news coverage. But Shayla didn’t recognize her cousin in the video. Not at first.

Family members always just called him by his middle name, “Perry.”

Now she was feeling a different sort of nausea. She retreated back under the covers. She couldn’t bear to look.

Floyd’s killing shocked a nation into grappling with long-ignored problems rooted in race, inequality and discrimination. It sparked worldwide protests during a global health pandemic. And soon, it would transform Shayla, 22, into an activist.

“A fire has been set off inside my soul,” she said in July after a protest in Lakewood, where she donned an orange mask that said “I can’t breathe” and held a sign demanding body cameras for all police officers.

But while Black Lives Matter protesters watched and echoed her public chants of “say his name,” they couldn’t see that Shayla, the daughter of a white mother and a Black father, had been suffocating under the pressure of her own years-long racial reckoning.

Was she Black?

Was she mixed?

Who was she?

“Where do I fit into this society? Where am I allowed to fit into this society?” she asked.

For decades, many multiracial women and men have grappled with these questions in the U.S. and throughout the world. Caught in the middle — never Black enough to be Black; never white enough to be white — some live their whole lives without coming to terms with their identity.

She didn’t know it as she curled up under her covers that morning in May, but her cousin's killing was about to help Shayla better understand her own place in the world.

Outsider

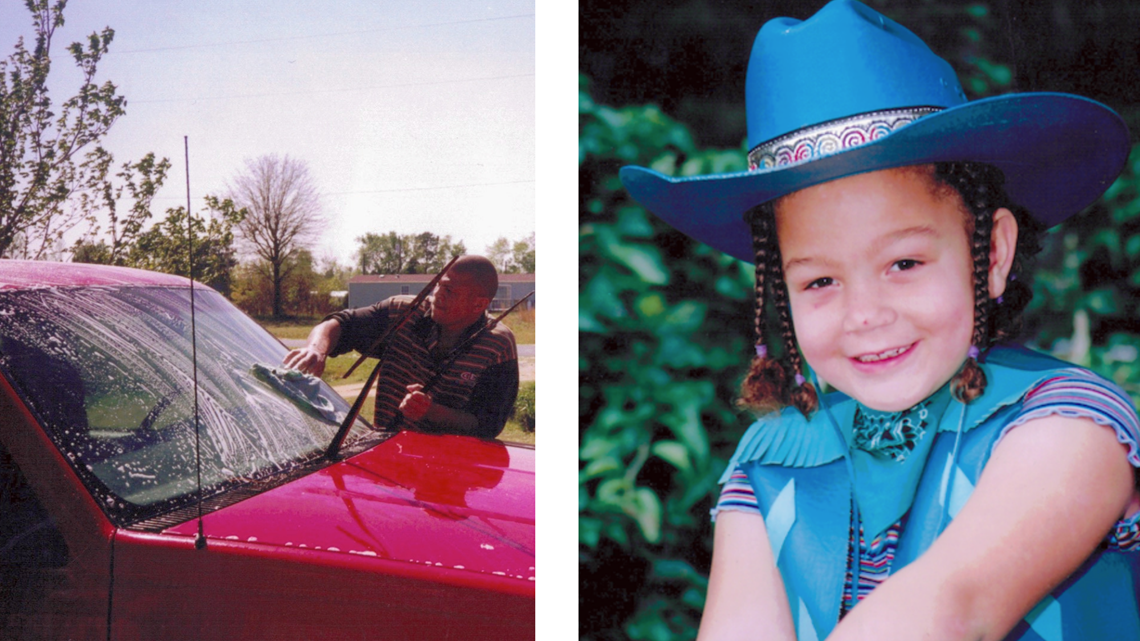

As a child, Shayla often fell asleep with a computer-printed photo of her dad, George Floyd’s uncle, tucked inside her pillow case.

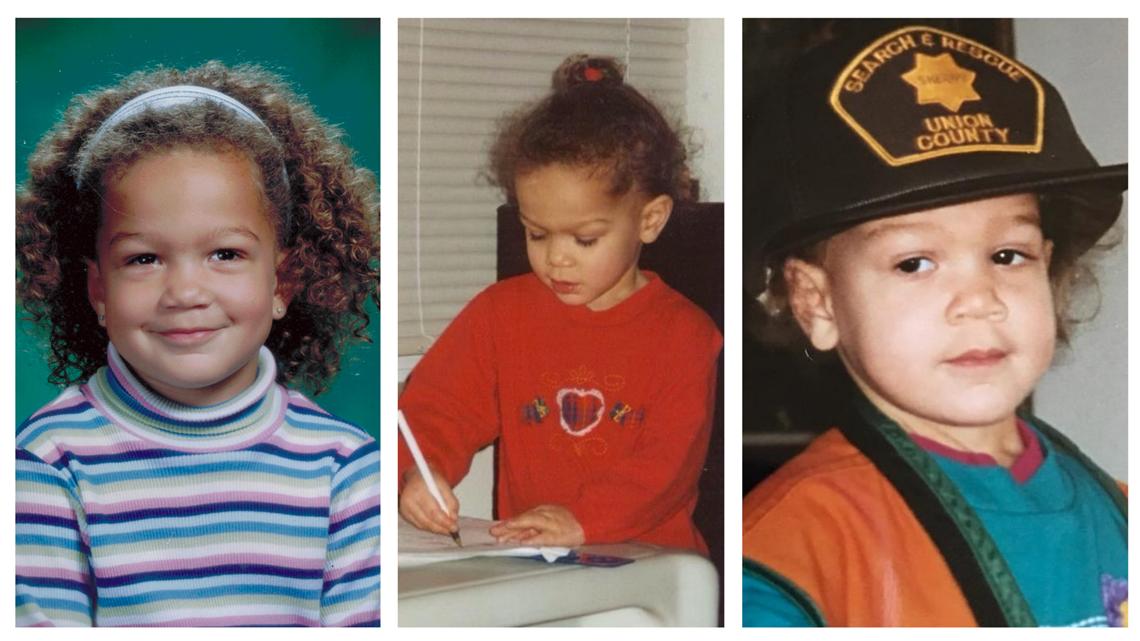

In elementary school, she curiously studied the photo, sometimes for hours. She didn’t know the man washing a red truck in the picture. Her mom left him before Shayla was born. Shayla often daydreamed about what it would be like to meet him.

She grew up with her white mother, who raised Shayla and her younger white half-sister, Kayleigh, in a three-bedroom house on a quiet cul-de-sac in Gig Harbor, Washington — across the street from a sheriff's deputy’s home and next to houses with gated driveways. The affluent Pierce County community is a popular tourist destination known for its scenic waterfront, upscale boutiques and gallery hopping. About 90% of the roughly 10,700 residents who live here are white. Less than 1% are Black, according to 2019 U.S. Census estimates. Even fewer look like Shayla.

“Just picture: You go into school and you sit down in your class in your little desk and you look around, and 100%, you were the only person who looks like you,” Shayla said.

“Your hair, your skin color, the actual physical color of you, your freckles, your eyes, whatever it is. You just look different than anyone else there.

“They all look the same, but you don't look like them.”

That picture of her dad, tucked into her pillowcase was the only tangible evidence of the other side of her family: the Black side.

Shayla first recognized she was Black in preschool when she saw herself in her class picture. Just she and one other student had dark skin.

“I got to a certain point where I understood I wasn’t white,” she said. “I didn’t know what I was. But I knew I wasn’t white.”

For most of her childhood, Shayla said, no one in her family acknowledged her skin color or the racism she would face because of it — not her white grandparents nor her mom, Kendra Zartman.

“Race never occurred to me. Honestly ... it was just never a thing,” Kendra said. “We’re a white family, and I raised her in a white family — not on purpose, not intentionally … I was just like, ‘People are people.’ There was no Black, white or anything.”

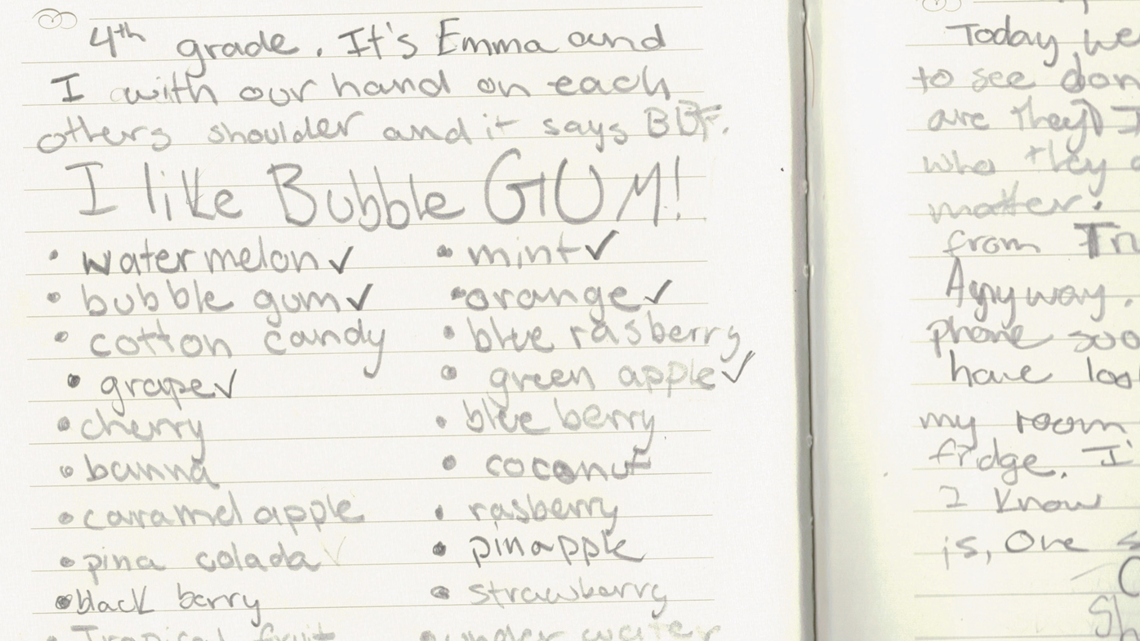

Shayla, at first, was too young to realize being biracial would define the course of her life. She spent her earliest days playing with her dollhouse, going on family camping trips and writing in her journal about her favorite song lyrics and her love for bubble gum.

Even though she didn’t talk about her race with anyone, Shayla would soon realize, the rest of the world couldn’t ignore it. White store clerks followed her while she shopped. Girls at school made jokes. Strangers called her the N-word.

“You can not consciously know that you are a Black person until someone says, ‘Why is your hair like that?’”

She wondered that, too.

‘They would literally pet me like a dog’

One afternoon in elementary school, Shayla grabbed her mother’s blonde hair dye from the cabinet under the bathroom sink. She lathered it across her dark brown corkscrew curls.

Instead of blonde, Shayla’s hair turned orange, one of her many failed attempts to look more like her mom, whose hair was long, straight and silky.

“I loved how I could run my fingers through her hair. I’d try to put a brush in my hair, and the brush breaks,” she said. “I wanted to have white-girl hair. I wanted it to be flat. I didn’t want it to be a big puff ball.”

Many Black women have distinct memories of their mothers styling their tresses. The ritual of hair combing, though it sometimes evokes physical pain, is often internalized as an act of tenderness that strengthens the ties between Black women and girls within the same family. Tiche Opland, a Black hair artist and educator who specializes in Black textured hair, said other Black people commonly view well-kept hair as a measure of how well a young woman is cared for.

“Your hair is your crown. With the different textures, there’s a status there. You would get more respect, you would be considered more attractive — more appealing to the eyes — when it’s actually put together. When it’s not, people will misjudge you,” Opland said. “I think the mentality goes back to slavery.

"When you talk about how (slaves) looked, that’s how they looked: neglected. So to see a (Black) child with hair that is all over the place and they don’t look put together, that’s the mentality we are drawing from.”

Shayla’s memory of her hair care is one of horror. It wasn’t a bonding experience for her mother, either.

“We would go for hours fighting over her damn hair,” Kendra said. “I didn’t know what I was doing.”

In Shayla’s early years, Kendra relied on a Black babysitter to take over all aspects of her child’s hair care. The sitter sent Shayla home in neatly-braided cornrows with a list of oils, lotions and additional hair products Kendra would need to buy in order to manage it herself.

She didn’t have a clue how to properly wash, moisturize and style her daughter’s hair. Sometimes it got so unkempt, Kendra said, she noticed Black women staring in the grocery store.

Shayla didn’t tell her mom—or anybody, really—why she so desperately wanted to straighten her hair or wear wigs. The candy wrappers, paperclips, pencils and erasers that some kids in class would stick into her thick afro was a painful secret. She never talked about how they called her “dirty“ because of her freckles and brown skin. Or how it felt to be compared to an animal when the other children touched her hair without asking.

“They would literally pet me like a dog and say, ‘Wow, you feel like a sheep,’ ‘Wow, you feel like a dog,’ ‘This feels like my carpet,’” Shayla recalled.

Kendra regrets it now, but she never explained racism to her daughter. She hadn’t considered that Shayla would ever experience it.

“She just is who she is to me ...This whole thing about her being Black and how it’s affected her life and stuff, I didn’t know,” she said. “I was just ignorant. Ignorant or naïve.”

Without her mom's explanation, Shayla struggled to understand why her classmates picked on her.

“My mom ... never said, ‘You’re different, and you’re beautiful because of that,’” she said. “I thought I was just like a bad kid … I thought I was just like a loser.”

On the eve of her fifth-grade class project, Shayla shut herself in the bathroom — again. But this time, instead of hair dye, she gripped a pair of red scissors in her hand.

Her brown curls fell to the floor as she took the first snip. She paused and looked at herself in the mirror, nervous about what she was about to do.

She continued to cut until every inch of the hair she’d come to hate was piled on the floor.

She felt free. But the feeling was fleeting.

‘I knew I was going to have to do it on my own’

The next day, Shayla waltzed into her fifth grade classroom dressed as Martin Luther King, Jr. — her hair clipped just as short as his.

She chose the costume for her history project, the first time in her life that she wanted to look like a Black person.

“I was grasping for something,” Shayla said.

She’d learned about Dr. King in a picture book, one she checked out from the school library in a private quest to understand her hidden heritage. She began to see the world in a new light.

“He died because people hated him because he was Black,” she said. “Someone killed him because he was trying to make things better for Black people.”

Shayla became obsessed with learning about Black history, though she kept most of her discoveries to herself.

At school, she learned about slavery. She wondered how she could find the same “power” and internal strength as the men and women who endured it. She sought out movies and History Channel documentaries about Black people. She read about civil rights leaders John Lewis, Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton. A poster of other influential African Americans — Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr. and Madam C.J. Walker — hung from middle school to high school on her blue bedroom walls.

Shayla still had so many more questions about who she was and where she’d come from. Questions that couldn’t be answered by history books and TV shows, and certainly not by anyone in her overwhelmingly white circle of friends and family.

“I was searching for the entirety of what it means to be Black. There are no specific words that you can use to describe it to someone,” she said. “Being a part of the culture, understanding our roots, where our family came from, understanding my family in general.”

She channeled many of her curiosities and her feelings into writing. She wrote in her purple journal almost every week, from fifth to seventh grade, as if the journal could respond.

“I’m going to start talking to you more. Only because I need someone to talk to,” she wrote in her journal at age 10.

“Oh I just had the best idea ever! You could come with me to school,” she wrote in another entry. “So during free time or lunch time, I can write in you.”

“Do you want to know something really cool though? I got blonde highlight. Me! With my curls. Haha it’s so cool.“

In the fall of 2008, Kendra called her 10-year-old daughter over to her desk with big news.

Shayla’s dad, Selwyn Jones, wanted to meet her.

Shayla couldn’t contain her excitement.

“I always wanted to cling to the Black side of my family,” she said. “I’ve always wanted to be Black because I’ve always known that I wasn’t white.”

About two months later, on a December night before she would hop on a plane to meet her father at his home in South Dakota, Shayla again clutched the photo she had studied closely for years.

“Finally,” she thought.

White

Shayla’s dad sent one of his coworkers to pick up his daughter from the airport.

As Shayla nervously waited to meet her dad, stepmom, her older half-brother Sean and another of her nine Black half-siblings, she caught herself again dreaming about what the man in the picture would be like in real life.

“Hi, I’m your dad. I’ve been looking forward to getting to know you,” Shayla imagined him saying.

She wanted a serious dad, a man to have heart-to-heart conversations with. Someone who could answer the questions that books and her white family members couldn’t.

The man she met however, was more of a fun-loving jokester. By the end of the first day, he was urging her to see how many grapes she could cram in her mouth at once.

“It was too much for me. His crude humor, his loudness. He was always making jokes. It was never about feelings. It was just about feeling good,” Shayla said. “I think that when I met him, and I realized he was not what I ever had imagined, that was a little bit disappointing.”

Within minutes of meeting, Shayla remembers her dad made a comment about the lightness of her brown skin.

“‘Oh my God, look how white you are … You look so white. You talk so white.’”

The words have lingered with her for years.

“It was very degrading to the experience that I was trying to capture,” she said. “I’m on this level of, ‘Wow, now I’m here with my Black family,’ and he said, ‘Oh, you’re white.’”

“I’ve never felt white. I’m like, ‘No, I’m not. I don't know what I am, but I’m definitely not that.’”

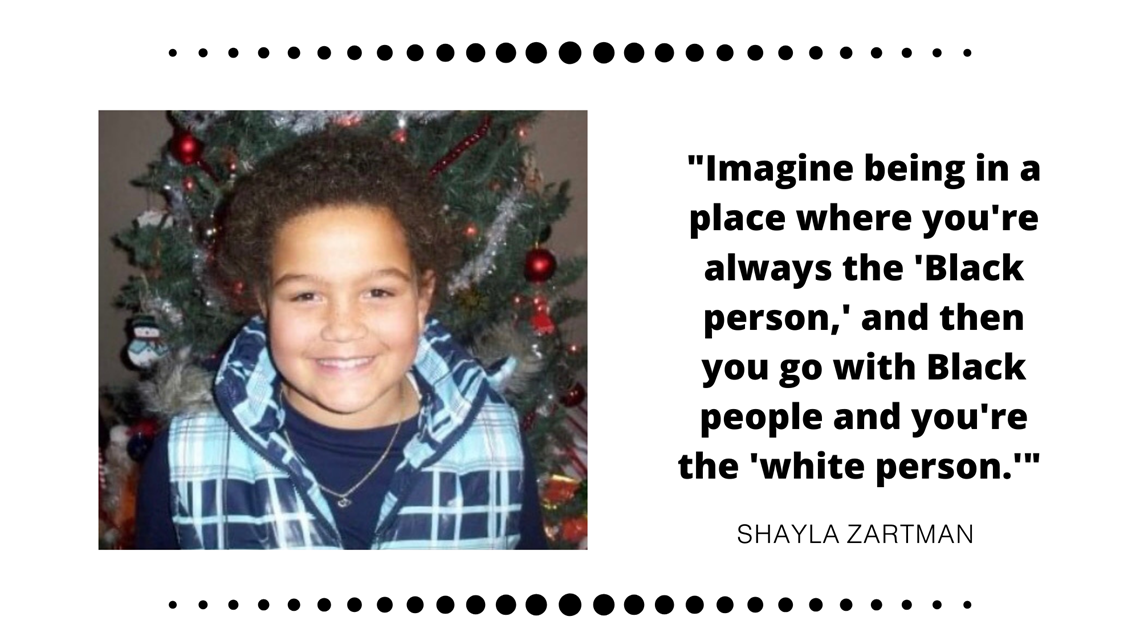

Despite her initial disappointment, Shayla and her father remained in contact after she left South Dakota. A couple years later, in 2012, they took a trip to Houston to meet her Black extended family members. She remembers the culture shock of joining their Thanksgiving celebration, where dozens of her cousins, aunts, uncles and other relatives boisterously gathered around spreads of food.

“Imagine being in a place where you’re always the 'Black person,' and then you go with Black people and you’re the ‘white person,’” Shayla said.

“You’re stuck in between in the middle all the time.”

Shayla didn’t understand their Southern slang, and she didn’t know what to make of the fact that everyone had a nickname, including her dad, whom they all called “Miles.” There was “Doll Baby,” “Pebbles,” “Bam Bam,” “Sugar Doll” and her cousin “Perry.”

That was the first time she met George Floyd.

To her dad, Selwyn, Shayla’s culture shock had a simple explanation:

“She was overwhelmed because she was like, ‘Oh my God. I didn't know there was this many Black people in the world, let alone in one house.'”

Shayla’s white friends and family members back in Gig Harbor had always joked that she was “too loud” as her animated laugh filled the room. Her teachers used to call her out. But here, as she sat quietly in the corner taking it all in, Shayla was intimidated by the volume of their laughter.

Here few people noticed her.

She wasn’t loud enough.

Writing

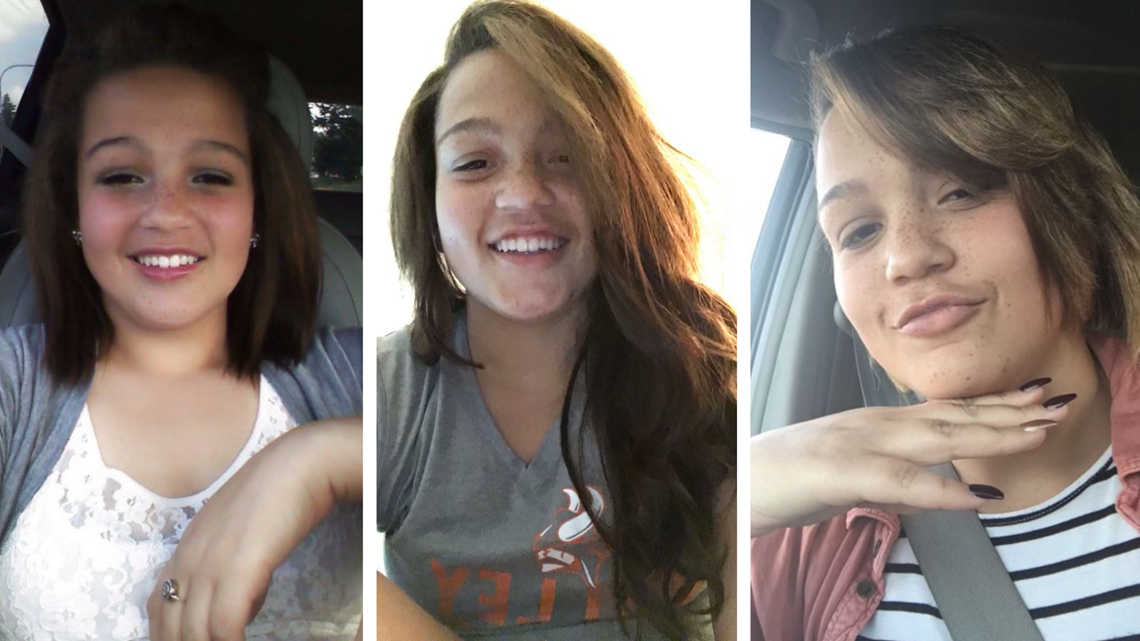

Soon after meeting her Black relatives, the little girl who once rambled on about bubble gum and her days at soccer practice was no more.

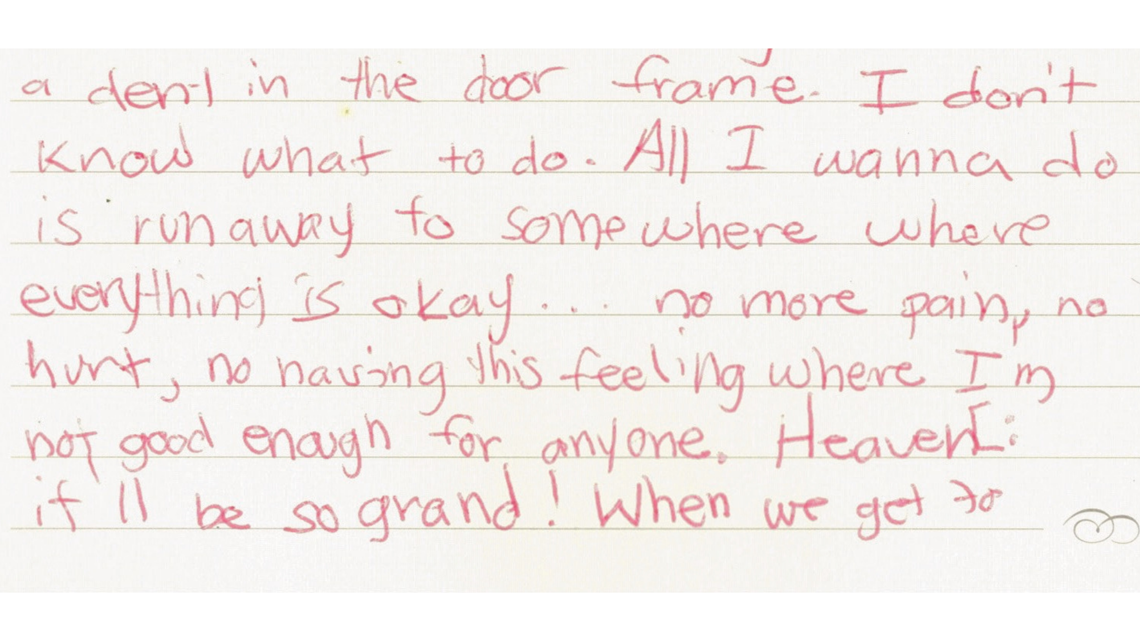

By middle school, Shayla began to struggle with depression. The tone of Shayla’s entries in her purple journal turned dark.

“When I write in red that means it's an emergency meeting,” 12-year-old Shayla wrote in one journal entry.

A couple pages later, red ink filled her journal.

“All I want to do is run away to somewhere where everything is okay ... no more pain, no more hurt, no having this feeling where I’m not good enough for anyone. Heaven: it will be so grand!”

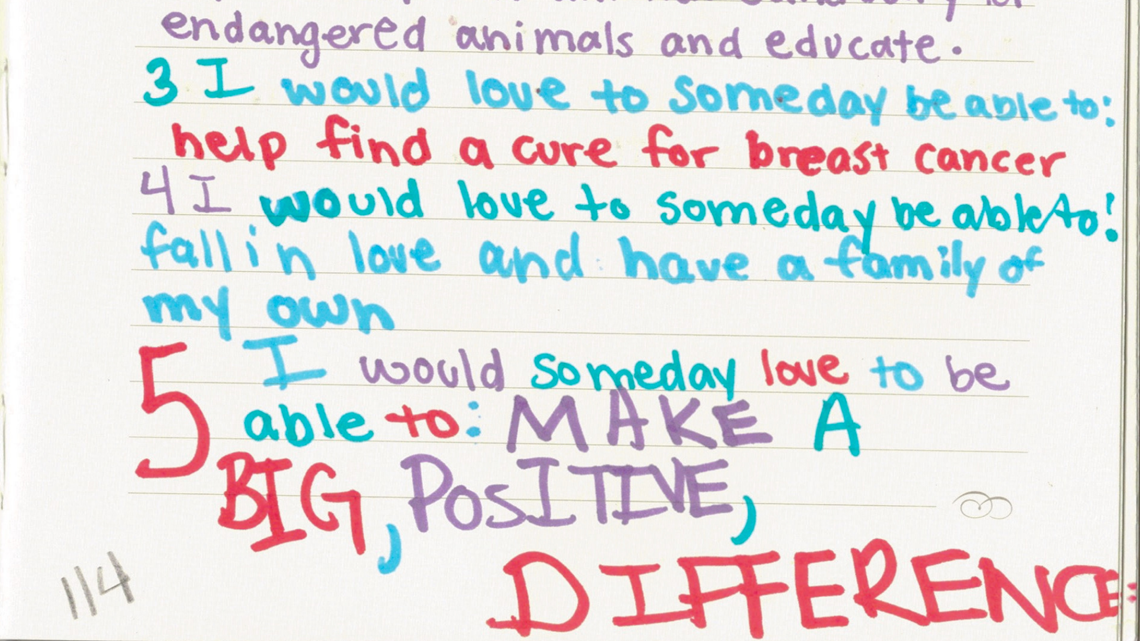

On good days, she replaced red ink with colorful markers. She made a five-item bucket list for her life before entering seventh grade: to travel the world, open an animal sanctuary, find a cure for breast cancer, fall in love. The fifth item, she wrote in all caps.

“MAKE A BIG, POSITIVE, DIFFERENCE.”

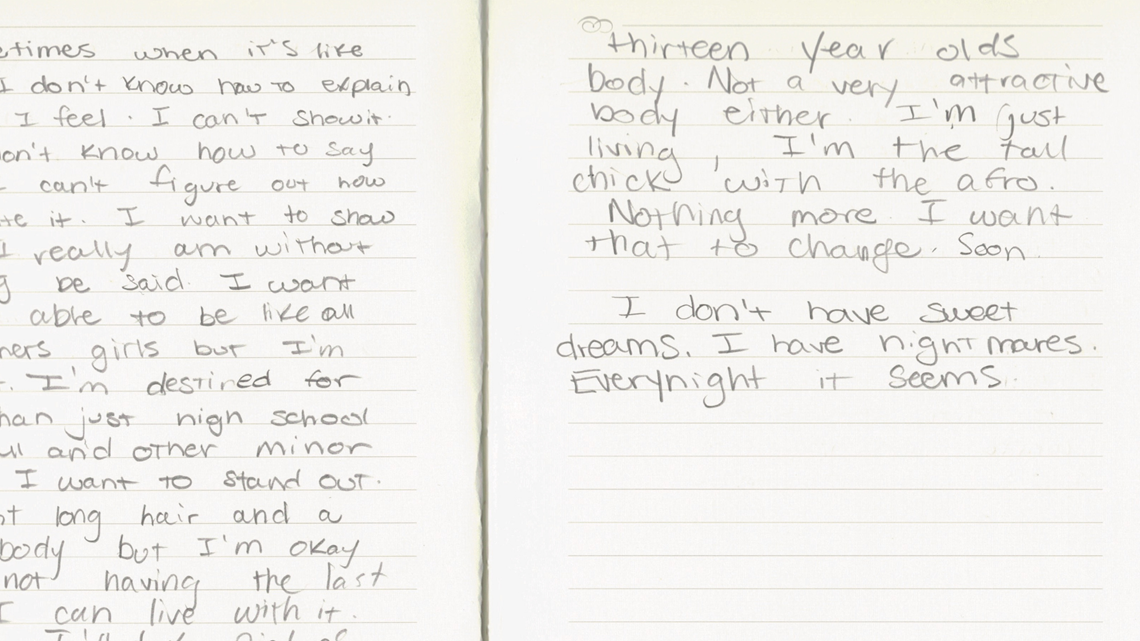

In one of the last pages, at age 13, she wrote about her biggest dream of all.

“I want to show how I really am without anything being said. I want to be able to be like all the other girls but I’m different. I’m destined for more than just high school volleyball and other minor things. I want to stand out. I want long hair and a tiny body...I want to grow up already.

“I feel like I’m a thirty-year old stuck inside a thirteen year old’s body. Not a very attractive body either,” Shayla wrote. “I’m just living. I’m the tall chick with the afro. Nothing more.

“I want that to change.

“Soon.”

WATCH: Shayla Zartman reacts to her childhood journal entries

Dropout

In middle school, Shayla sat near her friend, a male student who was the class clown. He was also the only other Black person in her eighth grade class.

Her friend was so chatty one day, Shayla said her white teacher paused the class and lashed out on him. Shayla vividly remembers the teacher calling the student a piece of “burnt toast” and warning that he wouldn't be successful.

Her friend stopped coming to class after that, Shayla said. He later dropped out of high school and got in trouble with the police, taking the same path of so many Black boys from school to the criminal justice system.

In Washington state, Black students are consistently disciplined at a higher rate than any other demographic. In the 2018-2019 school year, 8.3% of Black students enrolled in public schools were suspended or expelled for a discipline-related incident — more than twice the rate of suspensions or expulsions for white students, according to data from the Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI). Researchers have connected increases in school suspensions and expulsions to increases in incarceration rates and encounters with the juvenile justice system.

There are historic racial disparities in high school completion and dropout rates, too. Between 2014 and 2019, the high school graduation rate for Black students in Washington state was consistently lower than the graduation rate for white students, according to OSPI. In 2019, a higher percentage of Black Washington students dropped out of high school than the percentage of white students. Native American students had the highest dropout rate and the lowest graduation rate in the state.

Shayla pledged that she would never become one of those statistics. She would never follow her friend’s path.

“I have big expectations from myself,” she wrote in her middle school journal. “I plan to never go to jail, do drugs, become an alcoholic. I want to be successful. I plan to go to college.”

As one of the few Black students left in her school and the “token Black friend” in her white circle, Shayla said she felt enormous pressure to represent the “Black community” well. It was a message she also got from her mom, who had always urged her to check the “African American” box on her standardized tests so she could help boost the average test scores for other Black students.

But the hardest part of representing any group was trying to belong. And in her quest to belong, Shayla inadvertently perpetuated stereotypes.

“You have to navigate as a whole: Do I act differently when I’m with this group of people versus this group of people? Are white people going to say I’m being ‘ghetto’ if I tell the story the way I do with a Black person? Are Black people going to see me as being white if I talk about my classes?”

Deep down, she knew those generalizations about Black people and white people were all wrong. She knew that in her own mind she was also reinforcing them.

“People look for ways to discredit your identity, and when you’re in the midst of trying to figure out what that is anyway, it makes it really hard.”

As a freshman at Gig Harbor’s Peninsula High School, Shayla was an honor student who played tenor saxophone in the school band. She joined the basketball, swim and water polo teams. By her sophomore year, she was the water polo captain.

Like many high school girls, Shayla strived to look like her peers—from the ripped jeans and v-neck sweaters to the Ugg boots. For Shayla, that assimilation also meant she got her first weave — long hair extensions she could comb her fingers through and curl into glamorous beach waves.

But she couldn’t change her skin color. She couldn’t change how those she loved the most behaved without realizing the pain it caused.

She heard her mom, Kendra, say the N-word while singing along to a hip hop song. She noticed her grandfather take the side mirrors off his car and lock the doors in a predominantly Black neighborhood, but not in a white one.

She noticed white people often complimented her on how “well spoken” she was; how “pretty” she looked when she straightened her curly afro. She also noticed when her mother made comments, presented as compliments or jokes, that cut to her core.

Later she learned there was a word to describe those types of remarks: microaggressions.

“When (my mom) says stuff about my hair, she just doesn’t know how to say it, and it’ll come off as offensive,” Shayla said, adding that she rarely called out the behavior. “I was a singularity in their sea of whiteness, and I didn't want to cause a ripple.”

‘I became the stereotype’

Shayla was 13 when a neighborhood watch volunteer turned vigilante killed Trayvon Martin. She was almost 16 and learning to drive the year police officers killed Eric Garner, 43, Michael Brown, 18, and Tamir Rice, 12.

As an impressionable young person struggling to find herself in a racially segregated nation, those deaths resonated deeply. Being a teenager is tough enough. Being a biracial young woman in a largely white high school, in a largely white state, in a nation of increasing polarization around issues of race and unequal justice — sometimes felt insurmountable.

As she got older and learned more, the examples of how she said she didn’t fit in continued to mount. She learned that her driver’s ed training came with an extra chapter: “Driving while Black.”

It’s a rite of passage in many Black families for parents to have “the talk” with their children. It’s a talk about how their skin color could make them a target for police, and it usually includes a set of precautions: Be polite. Be cooperative. Always keep your hands visible. Don’t make sudden movements.

Shayla’s white family didn’t know to have “the talk” with her. So she turned to online videos for instruction about how to act in the event a police officer stopped her.

She also struggled to reconcile her white family’s privilege and “luxurious kind of life’’ with the extreme hardships, which included homelessness and hunger, that she knew some of her Black siblings faced.

“I felt that I wasn’t worthy of being the one in my family who got all this money and got to live this life. I had a roof over my head. I had food on the table,” she said.

Shayla couldn’t comprehend why she felt so bad when it seemed she had it all, while some of her Black relatives were struggling so deeply and her life in Gig Harbor appeared happy and carefree.

She felt guilt, shame, anxiety. And she just stopped.

“I was a good student. I was a good person. And then, I didn’t want to be that good person anymore. I just didn’t want to uphold the image that I thought other people wanted of me.”

By the end of her sophomore year, Shayla’s attempt to fit in became her downfall. She threw parties at her grandparents’ house when they weren’t around. She said she started drinking alcohol with friends and using drugs, like ecstasy and cocaine.

By junior year, Shayla quit going to classes.

“I became the stereotype,” Shayla said. “I became a number.

“Instead of ... being this Black person who scores well on their standardized testing, I’m now a Black student who dropped out.”

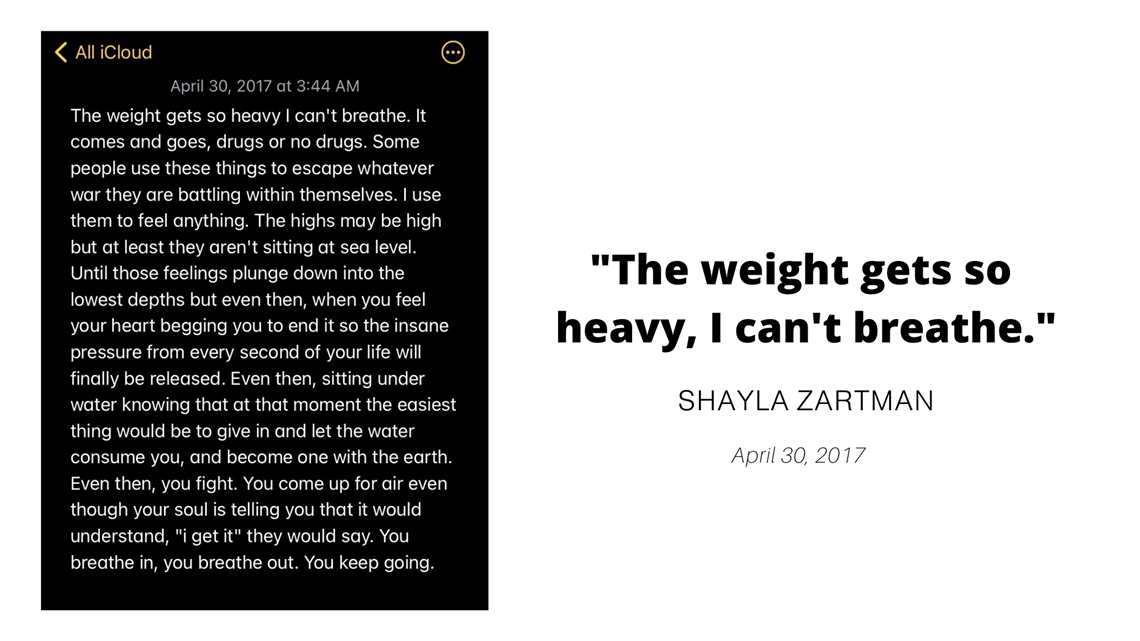

Shayla spiraled deeper into alcohol and drug addiction after leaving high school in January 2017, in the middle of her senior year.

“The weight gets so heavy, I can’t breathe,” Shayla wrote in her iPhone notepad in April of that year.

“It comes and goes, drugs or no drugs. Some people use these things to escape whatever war they are battling with themselves. I use them to feel anything.”

She moved out of her mother’s house and spent a few months couch hopping from Washington to California. In June 2017, at 18, Shayla moved in with her dad for almost a year in Gettysburg, South Dakota.

It would have seemed the trip was just what she craved: A chance to get to know her dad and more of her Black siblings. A chance to escape from the self-disappointment she carried after dropping out.

It turned into one of the most tumultuous years of her life, she said.

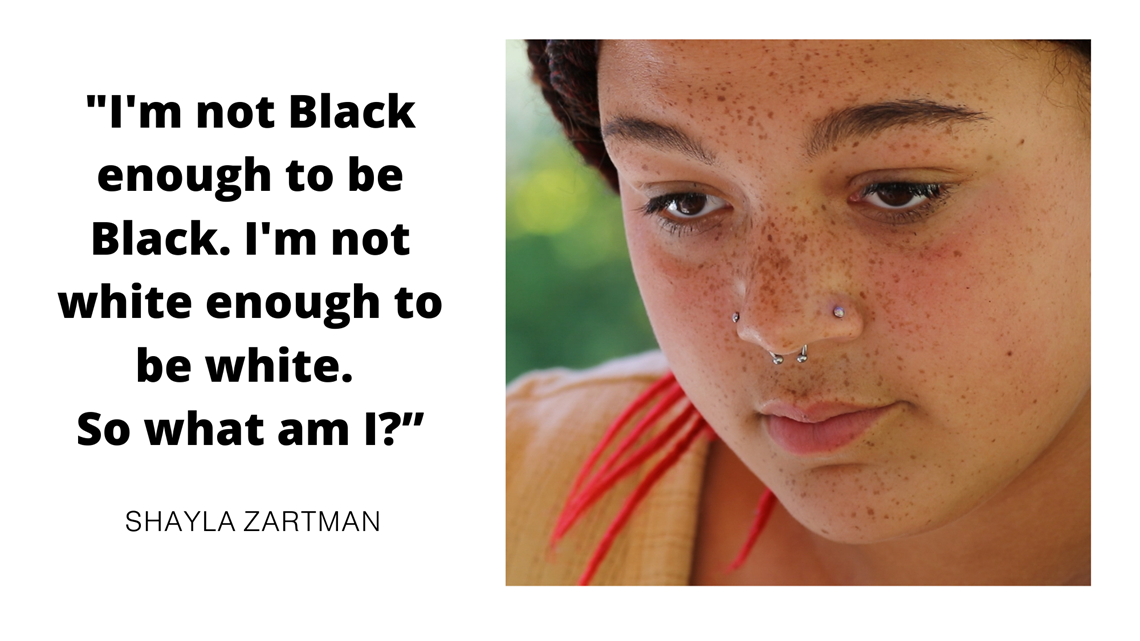

Shayla, at 19, returned to Gig Harbor in April 2018 with scars on her forearm. She’d been burning herself with cigarette lighters and cutting slits into her skin for months.

“I just hated myself,” she said, recalling her thoughts at the time. “I just feel like nobody understands me and nobody gets me and that sometimes I'm not worthy enough to be with.

“I'm not Black enough to be Black. I'm not white enough to be white. So what am I?

“I'm just nothing, I guess.”

In May 2018, two years before George Floyd was killed, Shayla grabbed her bottle of depression medication. She dumped significantly more than the prescribed amount of pills into her hand.

“I didn't want to kill myself. I didn't want to be dead,” she said.

“But I didn’t want to be alive either.”

Shayla swallowed the pills and closed her eyes.

Rebound

After her failed suicide attempt, Shayla spent a week in a psychiatric ward at a Tacoma hospital.

She started seeing a psychiatrist, who diagnosed her with borderline personality disorder and helped her understand why she was “so deeply sad.” One of the hallmark symptoms of this condition is a disturbed sense of identity, according to mental health experts.

Shayla said she got a handle on her addiction after that. She still drank alcohol socially and sometimes used marijuana. But she no longer relied on alcohol and drugs to cope, Shayla explained.

Slowly, she started to piece her life back together.

“It was like being at the bottom of a hike up a big-ass hill and just deciding I was ready to go for it and give it my all,” Shayla said.

She graduated from an alternative high school in 2019, the year she turned 21. Then she was accepted into college.

She was in the middle of her second semester of school this May, two years after she attempted to take her own life, when she got the text from her half-brother, Sean, that would give her life a clear purpose.

“Don’t watch the video,” he said.

Shayla texted her mom on May 26, the day she learned George Floyd died.

“My cousin in Minneapolis got killed by the police,” she wrote.

“Oh is that (who) that was? Oh honey, I’m sorry,” Kendra texted back.

Shayla couldn’t get to her Black relatives fast enough.

“I just had a feeling in my heart that I couldn’t handle,” Shayla said. “If anybody would be able to understand it would be them.”

She and Sean, who also lives in Washington, made the 20-hour drive to South Dakota the next day, as they waited for details about Floyd’s funeral services.

Shayla kept in touch with her mom as she drove across the Plains.

“How is your dad? Have you talked to him?” Kendra asked.

“He wants to protest,” Shayla replied.

“I want to, too,” added Shayla, who had never attended a protest before.

“I don’t want to die though.”

There would be funerals in each of the three states Floyd had lived: Minnesota, Texas and North Carolina. Shayla and her brother attended all of them.

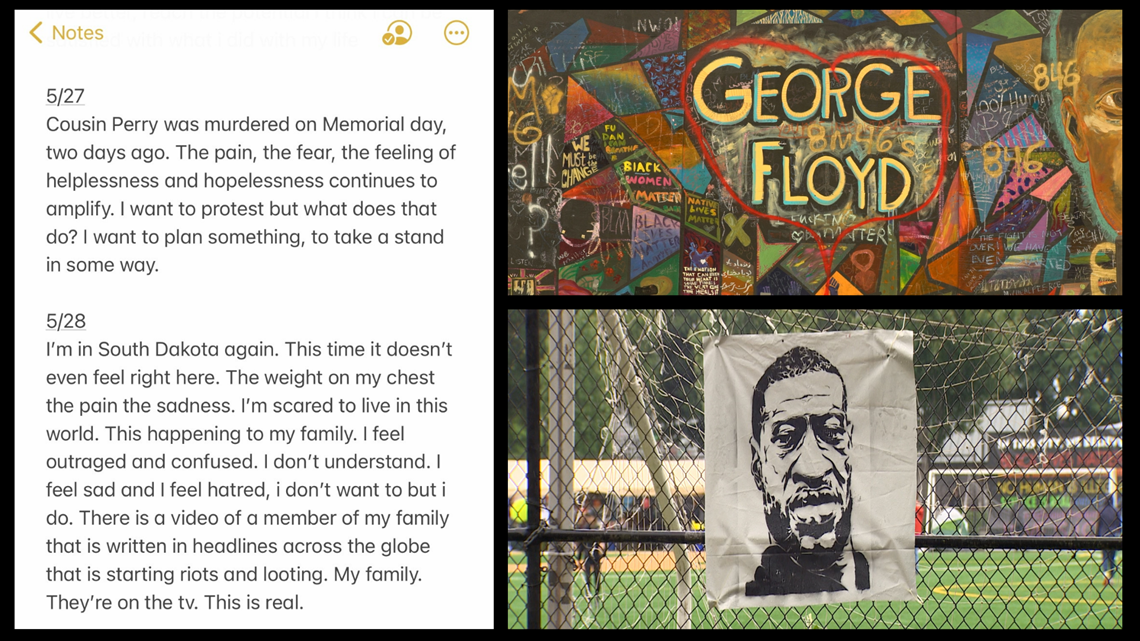

It seemed to Shayla that every stranger she encountered on her cross-country journey was talking about her cousin’s death and the protests erupting in response. She saw Floyd’s face on gas station TV screens, his name written in graffiti at bus stops, his face stenciled on sidewalks. People whispered about the video in convenience store lines and restaurants.

It was not easy to hear strangers say his name. To shout it in the streets.

“That’s my family member who just died, and it’s extremely difficult to not just have that anger boiled up in you at all times because I have to see it all the time,” Shayla said. “Every single time I go anywhere I have to see that and be reminded of what happened.”

Two nights before she would attend Floyd’s funeral in Minneapolis, Shayla turned on the news and sat in front of her dad’s TV, without emotion.

She watched as her cousins spoke on national news programs, as protests erupted in nearly every major U.S. city, as some smashed store windows and buildings burned, and as confrontations between police and protesters turned violent.

“I was completely numb, and I feel like I didn’t register what was happening,” she said. “I was like, ‘This isn’t real.’ I didn’t feel like it was real life. I’m like, ‘I know how to make it real.’”

Alone in the basement, Shayla pulled up the video on her laptop.

She watched all eight minutes and 46 seconds. She heard him call for his mother and tell the officers he couldn’t breathe. She watched as onlookers pleaded with the police officers to loosen their hold on him.

She watched as his body turned listless then lifeless.

She hopped in the shower, and for the first time since Floyd's killing, Shayla sobbed.

Broken Souls

Shayla texted her mom before the first funeral.

“I don’t think I can do this,” she wrote.

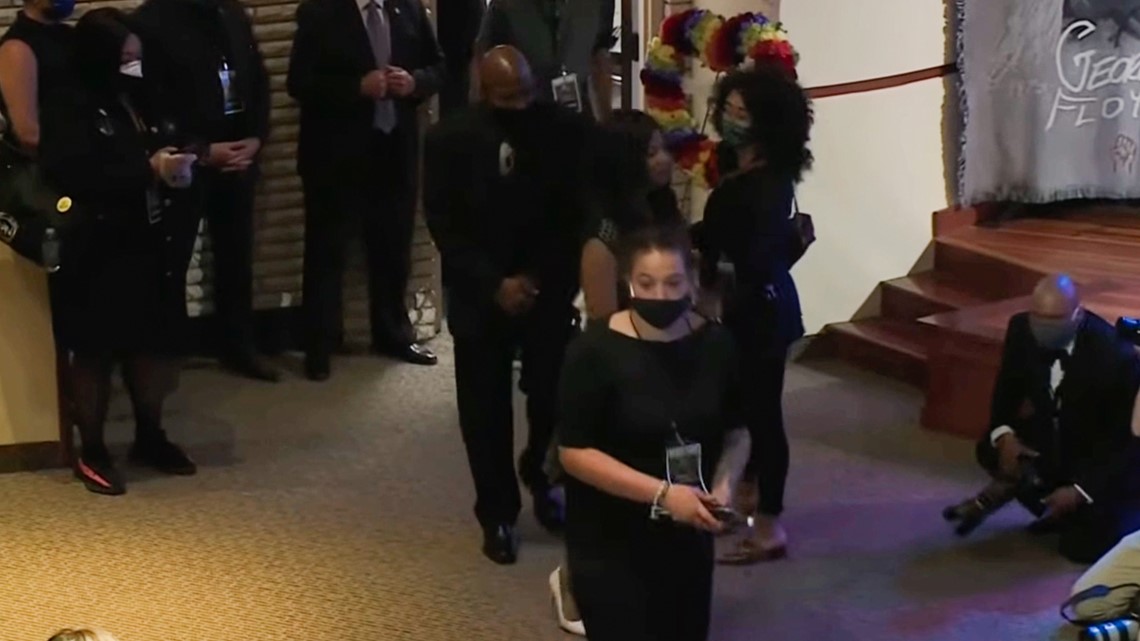

She was one of the first of George Floyd’s family members to enter the Minneapolis chapel at North Central University, where hundreds of mourners gathered on June 4.

She eyed the section of empty rows reserved for the family. It didn’t feel right to sit in the front row. She and Floyd weren’t close enough. So Shayla picked a spot in the second.

“I reverted back to those feelings of, ‘Oh, I’m just that kid in the corner again,’” Shayla said. “I was very scared that someone would tell me that I didn’t belong there.”

She still hadn’t come to terms with the attention thrust upon her family in just a matter of days — the legion of people drawn to the streets outside the chapel, the secret service agents, the limos, the worldwide news coverage. On the way to her seat, she passed celebrities Ludacris, Kevin Hart and Tiffany Haddish.

Then she spotted Al Sharpton, Jesse Jackson and Martin Luther King III, the oldest living child of the civil rights icon she dressed up as in fifth grade.

“Isn’t that crazy? Oh my God. It was unreal,” Shayla said. “It made me feel like I was a part of the next civil rights movement.”

She thought about the 10-year-old girl, who once read about those same civil rights activists while searching for answers about her Blackness. She thought about the significance of coming face-to-face with them a decade later.

“It made me really sad, too, to think about how long they’ve been doing this same thing — the amount of funerals and tears,” Shayla said.

It’s what came to her mind when she hugged Eric Garner’s mom after the Minneapolis service and later when she talked to the mother of Trayvon Martin in Houston.

“The pain and suffering they’re going through, they’re having to watch another family go through that again,” Shayla said. “When you’re a family member of a victim of police brutality, you’re stamped with that forever.

“I hope that we, like our little club of broken souls, I hope that we can stay exclusive.”

Shayla promised herself then she would make that her mission.

Black

On July 4, Shayla returned to the spot where Officer Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd. Chauvin faces charges of second-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter in Floyd’s death. His case is set for trial this coming spring.

Dozens of Black and white strangers gathered for a protest at Floyd’s memorial site, which was still filled with flowers, artwork and stuffed animals, in front of the boarded-up convenience store on the street where he died.

Shayla had marched in other protests in Washington and in other states after the funerals. But, until now, she never had the courage to speak.

She walked to the front of the group in Minneapolis and began talking. The loudly murmuring crowd hushed.

“This isn’t another Fourth of July to me. My cousin is gone! He’s gone!” Shayla screamed, as the crowd applauded throughout her course of the five-minute speech.

“This is enough!” she told the group.

Enough.

“How do we make a change? How do we stop this from happening to other people?” she asked. “I’ll tell you what I can do. I can be here right now talking to you guys, telling you my story. I can be at these marches.

“I can be in the streets.

“I can vote.”

In that moment, Shayla found her voice. It was the first time, she said, that she truly felt heard by white and Black people.

“In my wildest dreams, that’s the person that I dreamed of being — a person who’s confident about themselves with no exceptions and a person who stood up and was vocal and went out and fought for what they believed in,” she said. “I wanted to be a part of the movement that’s going to change the world.”

Confrontations, realizations and apologies

Shayla feels guilty that it took Floyd’s death to give her life purpose — a transformative awakening shared by untold numbers of Black and biracial men and women in 2020.

In the months after her Minneapolis speech, she has attended dozens of protests in Washington state and across the country, including the 2020 March on Washington in D.C.

She participated in virtual panel discussions, where she talked about fighting racism, where she learned about the ways in which racism was a systemic problem larger than just her individual experience. She spoke about police reform at a local university. She talked to her hometown police chief in a 20-minute phone call about the steps he was taking to protect the few Black community members in Gig Harbor.

“I think with George’s death, it allowed me to realize within myself that I have the power to talk to a lot more people and that I have the ability to talk to people really well,” Shayla said.

“So I should take that ability and go to talk to everyone because having the conversation is absolutely where it starts.”

That also meant going back to her mom’s house. It has meant sharing, for the first time, the struggle she had growing up Black in a white community. It has meant calling out racist statements that her grandparents make, pointing out microaggressions.

“Are you mad at me and grandma and grandpa for bringing you up in an essentially white world? That I didn't expose you to more, I didn't teach you more, I didn't make more things available to you as a Black person?” Kendra asked Shayla in August, during their first in-depth conversation about race. “There's been a few things that you've said that I've wondered, ‘Did I make mistakes?’”

“What were you supposed to do?” Shayla replied. “How does a white woman with a mixed child living in a white place, growing up in white place with white parents, how could you possibly have known?”

“I did not realize the depth of it until all of this happened,” Kendra acknowledged.

“‘Till George died?” Shayla asked.

“Until George died. Yeah.”

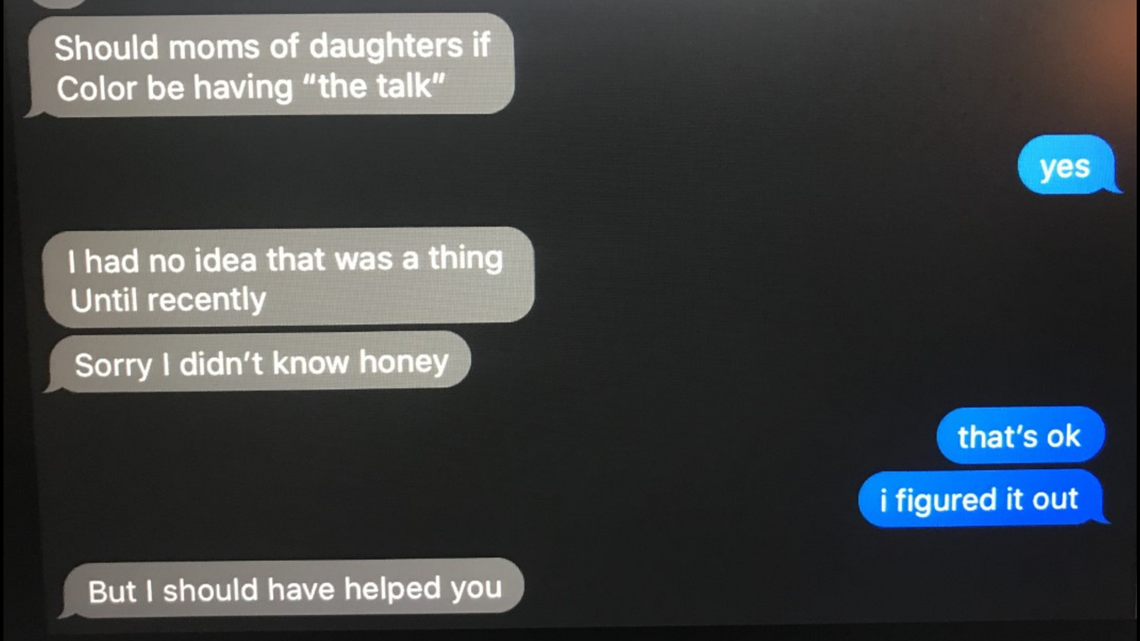

In September, Kendra asked Shayla a question after watching a news story about how Black children are taught to interact with police officers.

“Should moms of daughters (of) color be having ‘the talk?’” she asked in text.

“Yes,” Shayla responded.

“I had no idea until recently,” Kendra wrote. “Sorry I didn’t know honey.”

“That’s ok,” Shayla replied. “I figured it out.”

“But I should have helped you,” Kendra responded.

Shayla’s mom purchased a book a few days later. It was titled: So You Want to Talk About Race.

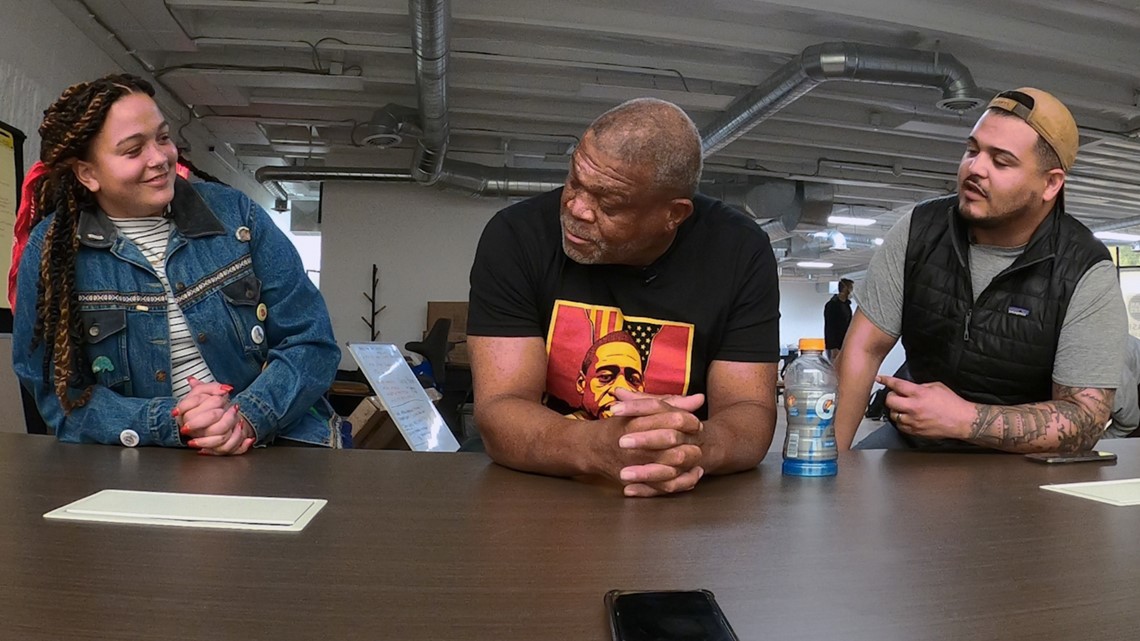

That same month, Shayla sat next to her half-brother, Sean, and her dad, Selwyn, in a Portland atrium, as they waited to participate in a panel about police reform. She’d been spending a lot more time with her Black relatives in the wake of her cousin’s death.

Selwyn looked at his daughter, who sat confidently with her hair in thick braids, and he told her she had “come home.” It was a comment about how she’d found her Blackness, how she embraced her hair as a Black woman, how she now presented herself as one.

Shayla had waited more than 10 years for her dad to say those words.

This fall, Shayla started making plans to switch schools. All of the top colleges on her list were historically black universities. After a lifetime in a predominantly white community, she’d decided it was time to learn and live in one that was predominately Black.

In November, Shayla walked into a Seattle tattoo studio.

“I want to use my body as a scrapbook in a way to document the things that I’ve been through,” she said.

She rolled up her sleeve to expose her left shoulder, on the same arm where a tattoo of a snake now covered up the scars from her self-induced cuts and burns.

She asked the artist to give her a tattoo of a woman.

But not just any woman.

A woman with Black skin, “full lips” and a “big poofy afro.”

Watch Shayla's Story

This mini-documentary originally aired in KING 5's Facing Race series on Dec. 13, 2020.

If You Need Help

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. It’s free, confidential and available 24 hours a day.

The Washington Recovery Help Line is an anonymous and confidential help line that provides crisis intervention and referral services for Washington state residents who are experiencing substance use disorder or mental health challenges. Call or text 866-789-1511.

TeenLink, a help line for Washington state teenagers, accepts text messages and phone calls at 1-866-833-6546.

How This Story Was Reported

KING 5 reporters followed Shayla Zartman over the course of five months. Details in this story are supported by more than 45 hours of interviews with Shayla and members of her family, in addition to a review of text messages, journal entries, photographs, video recordings and other source documents.

This story was produced as part of “Facing Race,” a KING 5 series that examines racism, social justice and racial inequality in the Pacific Northwest.

Contact The Reporters

Taylor Mirfendereski is a KING 5 investigative reporter, who specializes in multimedia storytelling, longform reporting and digital projects. Follow her on Twitter @TaylorMirf and like her Facebook page to keep up with her work. E-mail her at tmirfendereski@king5.com.

Christin Ayers is a KING 5 reporter and the executive producer of “Facing Race.” Follow her on Twitter @Christinayers5 and like her Facebook page to keep up with her work. E-mail her at race@king5.com.